Each paragraph steeps the reader in the itness of time, place, and relationship - the occurrences, smells, sounds, and emotions - of the memory.

It is his twentieth birthday and a friend he is secretly in love with arrives in his room and wakes him. He's bearing a bunch of rust-coloured chrysanthemums so big his arms can barely hold them. They plunge the flowers into a bathtub and search the town's charity shops until they find the vase they need, big-bellied, wide-necked. Back in his room they thrust the chrysanthemums into it just as they come, a rustling mass of leaves and waxy petals, curling like fakir's nails, above the sombre glaze, the same dull rust as the flowers themselves. Decades later, the flowers, which are flowers of death, are themselves long dead. But he still has the vase. He still has the friend.I love not just the sensations explicitly described by Lambert, but those suggested because the writing is detailed enough that I know where I am but spacious enough for me to fill in details with imagination. One such space is the secret love the narrator admits to carrying for the friend. Inference here is better than knowing because the reader is active in wondering. Lambert's form requires economy, leaving room for for me to create what he does not mention - the feelings and hopes invested in the secret, the crinkling of the cone which holds the chrysanthemums, the coldness of the water in the bathtub, the coffee the friends drink prior to their search for the vase. They are not Lambert's memories, they are my projections upon his memory. I invest belief is his fiction by, in some way, making it mine.

His father buys him a bicycle, but it is the wrong sort. The bicycle he wants has swept-down racing handlebars and no mudguards and is green and white. This one has small wheels and can fold into two. It is the colour of bottled damsons. He pushes his new bicycle into the road and rides away as hard and fast as he can, but it is not fast enough; it will never be fast enough to escape the shame of the thing that bears him. His eyes are blinded by tears. When he skids and scrapes the skin from his arms he is glad. He shows his father the blood. This is your blood, he thinks but dare not say.I was struck by how many memories Lambert captures of betrayal and shame, particularly in his protagonist's younger years. Certainly these are experienced in any life, but I felt in reading a recognition of what it means to grow up gay in a world of mostly straight people. This is not about overt mistreatment, although that happens too, just about the fact that most people's mysteries about themselves seem to receive solutions in the roles and rites offered by society. Mine did not. The sensitivity ascribed to so many gay people may have its origin in this repeated sense you have disappointed others and anger at feeling disappointed in oneself as if, if you did not find the solution as others did, there must be something wrong with you. I felt a kinship with the way Lambert captured the small betrayals of childhood.

Lambert is by no means fixated on the negative. His episodes are filled with tenderness, especially for his parents, as well as art, sex, mystery, and mundanity. The life of his protagonist is the sum of all these experiences. This protagonist could be Lambert himself - who is also male, gay, British-born, living in Italy with a man named Giuseppe. The author acknowledges that his friends and family appear in the book. So, are we reading memoir? Perhaps, but we are reading the creation of Lambert, known for writing fiction, who is exploring form through what appear to be memories. And Lambert writes

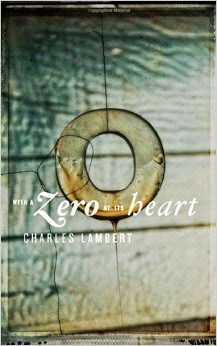

The last thing he wants to do is read about himself. He can't understand these people who talk about identification with characters, as though books were some sort of police line-up in which the culprit, oneself, is concealed among the rest, who have nothing to do with this crime, whatever else they might have done, and the game is to worm oneself out and say, yes, that's who I am.In reading With a Zero at its Heart, I found it less important to know if these episodes were from Lambert's life than to notice that I was convinced that they were. What the reader experiences is not a confession, it is a crafted thing, a work of art whose subject was how the contents of a life add up to a self. It is as though, with this tight, attractive object, (I am so glad that I did not read an e-book format) Lambert uses himself to contemplate the idea of 'self.' We like to think of ourselves as something definitive - to whom this happened and then that happened, and that's how we ended up who we are. We like ourselves to have a narrative through-line, but this throughness is something we make up every time we wonder 'why?' Something made for the sake of a coherence that we crave. It is merely one story of self, but we know that there are others. Our version of ourself is different from others' versions of us. Our own version of our self at 16 is different from our version at 50. Here Lambert lays bare the illusion of throughness by undressing the story, sifting through the separate episodes of a life as though each were a cherished object sorted in little boxes labelled "colour," "cinema," "hunger." He devotes 120 words to some essence of each, as though having received instructions, yes, you can pick this up, but don't linger.

This question of how much of an author makes it into a book fascinates readers now (and it didn't always), as art making is more and more intertwined with celebrity, giving audiences the sense that, if someone has created a work, they have offered themselves de facto as public property. Take the drama surrounding the Italian author who has taken the pen name Elena Ferrante. Her refusal to give interviews and intertwine her private life with her art (even though her narrator is also named Elena and comes from Naples) is given as much space as consideration of characters, plot, or writing, even in venues like the New York Review of Books. Ferrante's compulsively readable saga of the friendship of two Neopolitan women, so different from Lambert's book, shares this consideration of author as storyteller and the question of the influences which make up character in art and life, but while Ferrante crafts a multi-volume novel in the most popular of forms, Lambert's compact fiction is a work as interested in form as in content - an experiment.

He's presented with three white mice in a plywood box, divided by a wall with a zero at its heart. The smaller part has newsprint shredded for bedding, the larger an exercise wheel and canisters for food and water. The front of the box is panelled with glass. He hopes his mice will breed...I couldn't help thinking of this episode, from which the book takes its title, as containing the book as a whole. The box of mice are an experiment - like the book - in which cherished things are observed living, but as if through glass. That glass creates distance between us and what happens, since memory doesn't exactly replay what happens. Neuroscience understands remembering not like reaching into the of neural equivalent of a drawer, a retrieving of whole episodes as though they were a collection of antique postcards which have lain there unchanged from the last time we looked at them. Rather, the neural imprints of our sensory experiences, encoded in many different places across the brain, are animated anew - a creative act like Lambert's. In this new context, I imagine that past events and people are tinged with meanings only available to our present self, as well as a sense of distance from what we know is now past. Lambert finds the poignancy and longing of that distance in With a Zero at its Heart and in the struggle created by the limits of form he sometimes seems to touch the essence of what has passed.

No comments:

Post a Comment