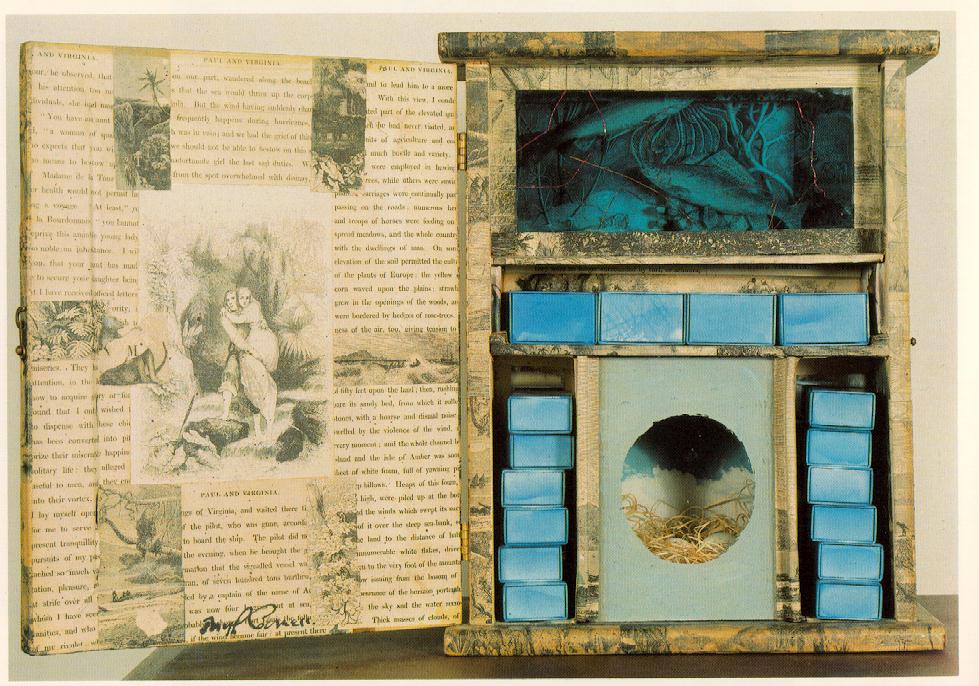

Who else but Stephen Sondheim would write an entire act of a musical in which nothing happens except an artist attempts to see and paint a picture. But that artist is pointellist Georges Seurat and that picture is Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte and the musical is Sunday in the Park with George and so much happens in it. The work is in some ways a grand undertaking - it is about the artist's vision and the artist's role, it is about creative process, the prices and rewards of obsession, it about the perseverance necessary to go against the grain, it is about the acts that give life value. It is a grand undertaking presented but presented in an intimate rather than opulent production - if it's big Broadway you're after you will not find it here. The actors playing Georges (Daniel Evans) and Dot, his model (Jenna Russell) give honest and nuanced performances. Their singing voices are not flashily beautiful. The unit set is spare and functions as a blank canvas, imagine that, on which the show's settings can be painted (or projected in this case). The orchestra has only a handful of musicians in it. I appreciated how the characters other than Georges and Dot operated in a usual sort of Broadway idiom - the scale of their performances is a bit larger, they operate more as types - so that every time the actions returns to Georges or Dot, the lens seems to zoom in and we are in a room with them. The production uses theatrical form to talk about artistic form and I found that apt. In the first act, as I mentioned, we witness Georges Seurat painting his famous Sunday in the Park..., in the second, it is 100 years later in the gallery in which the painting hangs. A contemporary artist, also named George, makes an homage to his artistic predecessor involving his grandmother (Dot's daughter, perhaps the child of Seurat) and tries to figure out what his work is all about. He tries to find the courage to create what he wants instead of what he thinks others want of him. At some level we all play out this struggle of our individual wants against current of what others expect and demand of us. In that way this show is very universal. The music makes use of an appropriately narrow palette, I've always thought it referenced French classical music. I love the way this Sondheim work sets text to music, it is relentlessly speech-like. It has a very - talked-on-the-note sound to it. The one now well-known song, Putting it Together, immortalized by Barbara Streisand's Broadway Album is, to my ear, the one trite bit of music in the piece. This production did not convince me otherwise. But I love Dot's two songs - Sunday in the Park with George, in which she complains of the inconveniences and indignities of posing for the famous artist, and Everybody Loves Louis - as she tries to justify to herself leaving a famous artist for a well-loved baker. George's Finishing the Hat is a beautiful anthem to his obsessiveness, his determination to see, to recreate what he sees in a way that the viewer of the painting (even 100 years later) becomes complicit in creating with him. Seurat made use of the optical science of his day, that observed that two colors just overlapping can have the appearance of a third and different color when seen from a distance, and this gave birth to pointillism. If you look at the "black" hat, the "white" sail or the "green" leaves in Seurat's paintings, you see that they are each really composed of multiple colors. One can stand up close to the paintings and observe the composition of the colors as the forms fragment - like looking through a rain spattered window - or one can stand further away and that distance allows us to see whole forms with illusions of single colors that our eyes create. The paintings use not the perspective of the classical painters trying to render architecturally faithful reproductions of scenes on their canvases, but make one aware of how perspective is a tool that can help us see different elements of the world depending on where we stand. Sondheim's musical also uses perspective with two acts spaced 100 years apart, one in which a ridiculed maverick messed up any opportunity for a career by not painting what was expected of him and ended up alone by not living as he was expected, another in which that famous painter - his value now understood - attracts the donations of millionaires, the serious criticism of cogniscienti, and the appreciation of ordinary art lovers too, as a new generation of artist struggles with this battle of personal vision and the pressures of public opinion. The finale of both acts I and II are company numbers in which the spare melodic palette of the other songs, and the exchanged lines usually of solo voices blossom into a rousing chorus dense with harmonies and the previously white stage is saturated in the colors or the painting as each George creates his Sunday - they let you feel the ultimate satisfaction of creating a work and they are very movingly composed and staged.

It's a pity that MOMA's exhibit of Seurat's drawings is not still up. But if you will be in New York City before the end of June, get some tickets for Sunday in the Park with Georges and then spend a day at the Museum of Modern Art or the Metropolitan and take a look at some of Seurat's drawings and paintings and see if you see them as you looked at works of art before.