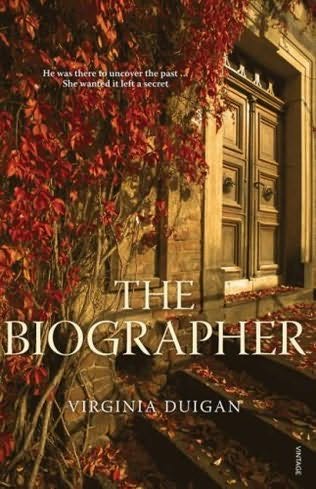

I have always thought I would like to write someone's biography one day, since I enjoy reading them so much. I even have someone in mind. That's probably why the plot description of Virginia Duigan's The Biographer so intrigued me. Greer, an Australian woman, is swept off her feet by Mischa, a Czech painter whose work is being shown at the gallery at which she works. Cut to 25 years later, said woman and said painter live in Italy on an old vineyard, sharing the group of old buildings with Rollo and Guy a couple, one paints and the other makes wine. Antony, who is writing Mischa's biography, comes to visit them. Greer is very uncomfortable about Antony uncovering her past, so the biographer's visit precipitates a spate of remembering, going through old diaries and letters, which is how we learn her story. Is there some bigger, darker secret troubling her or is she just uncomfortable because she left her husband to be with Mischa? I'm not sure. But the impending arrival and then the visit of the biographer is certainly creating disquiet for Greer a third of the way through this story. I had ordered this book to take with me on vacation, but I'm glad I'm reading it now because I'm feeling luke-warm about it. In the opening chaper, I had a very hard time keeping everybody's name straight. The story was hopping back and forth in time, casually mentioning people by name and I didn't know yet who they were. That straightened itself out. Duigan writes clear characters without writing caricatures, which I appreciate. The aging queen vintner, the crazy Polish housekeeper, and she really has the selfish artist down. Mischa is every inch the charismatic, unshaven, self-centered brute he should be. Here is her description of Mischa's painting:

I have always thought I would like to write someone's biography one day, since I enjoy reading them so much. I even have someone in mind. That's probably why the plot description of Virginia Duigan's The Biographer so intrigued me. Greer, an Australian woman, is swept off her feet by Mischa, a Czech painter whose work is being shown at the gallery at which she works. Cut to 25 years later, said woman and said painter live in Italy on an old vineyard, sharing the group of old buildings with Rollo and Guy a couple, one paints and the other makes wine. Antony, who is writing Mischa's biography, comes to visit them. Greer is very uncomfortable about Antony uncovering her past, so the biographer's visit precipitates a spate of remembering, going through old diaries and letters, which is how we learn her story. Is there some bigger, darker secret troubling her or is she just uncomfortable because she left her husband to be with Mischa? I'm not sure. But the impending arrival and then the visit of the biographer is certainly creating disquiet for Greer a third of the way through this story. I had ordered this book to take with me on vacation, but I'm glad I'm reading it now because I'm feeling luke-warm about it. In the opening chaper, I had a very hard time keeping everybody's name straight. The story was hopping back and forth in time, casually mentioning people by name and I didn't know yet who they were. That straightened itself out. Duigan writes clear characters without writing caricatures, which I appreciate. The aging queen vintner, the crazy Polish housekeeper, and she really has the selfish artist down. Mischa is every inch the charismatic, unshaven, self-centered brute he should be. Here is her description of Mischa's painting:I looked at the picture. It was of a piano in a paddock. Standing on the keys, feet apart, was a little barefoot Aboriginal girl dressed in oversized dungarees, staring the onlooker down with a truculent expression. She and the piano were painted very beautifully and meticulously. The paddock was reocgnisably Australian - brown, parched, with a huge expanse of blue sky and an extraordinary atmosphere of heat and blazing light - all that was painted very freely and expressively.It's all very nice, but I haven't quite figured out why Greer is in such a tizzy. I find myself liking them all, except for Antony of whom I am suspicious, and that is as it should be. But so far Greer seems to be making a great deal out of not very much and I'm not sure why I should care. They are an entertaining enough bunch, Duigan moves skillfully between time periods, perhaps I am missing a cruicial piece of information, but right now it just seems to be a story about a woman who likes her private life to be private. We'll see what unfolds.

In the meantime, I have ordered a slew of books from the Book Depository and I really hope they arrive in time for our trip. Time to get to work on finishing my last paper of the semester.