Literature good and bad, theater,and neuroscience....no really.

This is my first encounter with best-selling British writer Sebastian Faulks. So far his latest, A Week in December, reads like a restless montage of contemporary ephemera - a literary equivalent of, say, the film Crash - reflecting the breadth of contemporary London life and its preoccupations - credit default swaps, multiculturalism, gaming with on-line avatars, and terrorism. He quick-cuts between segments (of substantial length) from the lives of a young woman who is a train-driver on the London underground, a hedge-fund manager, a young man in an islamist terrorist cell, a teenager who does nothing but smoke pot, eat pizza, and watch so-called reality television, and a few others, following their lives over a single week as their existences slowly converge in what feels likely to be disaster. This Robert Altmanesque technique does not shortchange the reader on detail within the individual segments. In fact, Faulks has accumulated scads of them which, as I read, I can't help thinking of how mind-numbingly specific to our own time they will become in about five minutes. Yet, the meta-story is told the through the confluence of these stories, which make for their own evocative rhythm that feels as though the segments are being viewed on simultaneous screens - hence the allusion to Crash - and whose appreciation is not particularly harmed by missing any particular detail of an individual segment.

This is my first encounter with best-selling British writer Sebastian Faulks. So far his latest, A Week in December, reads like a restless montage of contemporary ephemera - a literary equivalent of, say, the film Crash - reflecting the breadth of contemporary London life and its preoccupations - credit default swaps, multiculturalism, gaming with on-line avatars, and terrorism. He quick-cuts between segments (of substantial length) from the lives of a young woman who is a train-driver on the London underground, a hedge-fund manager, a young man in an islamist terrorist cell, a teenager who does nothing but smoke pot, eat pizza, and watch so-called reality television, and a few others, following their lives over a single week as their existences slowly converge in what feels likely to be disaster. This Robert Altmanesque technique does not shortchange the reader on detail within the individual segments. In fact, Faulks has accumulated scads of them which, as I read, I can't help thinking of how mind-numbingly specific to our own time they will become in about five minutes. Yet, the meta-story is told the through the confluence of these stories, which make for their own evocative rhythm that feels as though the segments are being viewed on simultaneous screens - hence the allusion to Crash - and whose appreciation is not particularly harmed by missing any particular detail of an individual segment.She had not gone far before she encountered a man. He had cargo pants to the knee, bare torso and multiple piercings. His skin was light brown, though most of it was covered in tattoos; he carried a Uranium credit card (the highest rating) and a submachine gun in his right hand.Finn, the teenage TV addict watches a television interview with a schizophrenic:

Jenni sighed. This was not the kind of man she would have chosen, but she had learned that it was pretty much standard dress for men in Parallax. Most of the maquettes were scary and you just had to remind yourself that they might in reality be women or children - you absolutely could not rely in appearances; you had to disbelieve your eyes.

For the last fifteen years, Alan had been without a permanent home. He said he hadn't liked the hospital, it was loud and dirty, but at least he'd felt safe there.

"So," said Terry O'Malley, "as far as your accommodation's concerned, it seems you're in two minds about it."The characters in these parallel stories watch television to get the stories of real people, but they don't actually listen to them. They connect to tattooed gangsters and don't really know who they are. This is a world about being disconnected from each other and from our senses - the equipment that we have to collect information about the world and make predictions about behavior given what we can know about what exists outside of us. The only people alert to the details of their surrounds in this novel are those who want to place bombs in public places or who wish to make personal fortunes at the cost of billions in others' pension investments. This is our world, in case you didn't recognize it.

The audience laughed. "Schizophrenia...in two minds..." O'Malley underlined his joke for the slower ones.

"That's not what schizophrenia means," said Alan. "That's a misunderstanding. It's nothing to do with a 'split personality' or -"

"Sorry," said Barry Levine. "Which one of you said that?"

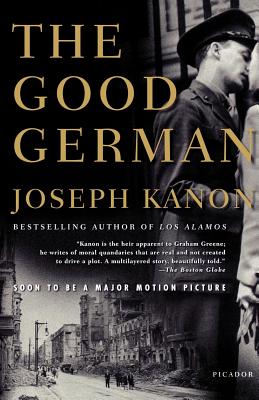

Joseph Kanon has been compared to Graham Greene, and having just read The Good German I can see why. He explores moral questions in a context where the political meets the personal but does so in a format that is recognizable as entertaining - the thriller. Kanon's plot doesn't baby the reader. It is intricate and he does not over-explain the action in a step-wise fashion - a quality I appreciate. Instead, events unfold fluidly through behavior and dialogue, their ambiguities intact. The setting of The Good German is just post-World War II Berlin. The concentration camps have been emptied. Berlin is rubble and the British, the Americans, and the Russians have carved it up into zones and are struggling over how justice can be wrought on the Germans. That's the political part of the story. Into this setting falls the body of an American soldier. No one knows who murdered him or why but a great deal of money is found on his corpse and American reporter Jake Geismar is not content to leave the story alone. That's the mystery/thriller aspect of the story. The book asks one question, the Germans were clearly responsible for the war but who do you hold accountable? The military sent to Berlin to clean up the mess seem to find that, beyond the Nazi party leadership and the camp guards, everyone else seemed to have been following orders or trying to stay alive. No ordinary individual German seems to think they had any culpability. Is a greifer (a spy who turned Jews and other criminalized groups in to the Nazi's) guilty? Even if they are Jewish themselves? How about a scientist who collected statistics for the experiments conducted on unwilling human subjects in the camps? That is the moral part of the story. In addition, Geismar left behind in Berlin a married woman with whom he had an affair and wants to know if she is still alive. That's the love part of the story and in Kanon's hands these four threads of this book blend unselfconsciously. His prose is entertaining but not too brisk at the outset. He takes his time developing the stories and their actors. His dialogue is clipped, sparse, and believable, the moral and political ambiguities are neatly plotted and make good drama, the history is accurate and detailed, and he is good at suspense too. In the last 100 pages there is a terrific escape and chase scene - a real white-knuckler. This is a book that just screams movie - and evidently it was made into one, although I haven't seen it. Have any of you?

Joseph Kanon has been compared to Graham Greene, and having just read The Good German I can see why. He explores moral questions in a context where the political meets the personal but does so in a format that is recognizable as entertaining - the thriller. Kanon's plot doesn't baby the reader. It is intricate and he does not over-explain the action in a step-wise fashion - a quality I appreciate. Instead, events unfold fluidly through behavior and dialogue, their ambiguities intact. The setting of The Good German is just post-World War II Berlin. The concentration camps have been emptied. Berlin is rubble and the British, the Americans, and the Russians have carved it up into zones and are struggling over how justice can be wrought on the Germans. That's the political part of the story. Into this setting falls the body of an American soldier. No one knows who murdered him or why but a great deal of money is found on his corpse and American reporter Jake Geismar is not content to leave the story alone. That's the mystery/thriller aspect of the story. The book asks one question, the Germans were clearly responsible for the war but who do you hold accountable? The military sent to Berlin to clean up the mess seem to find that, beyond the Nazi party leadership and the camp guards, everyone else seemed to have been following orders or trying to stay alive. No ordinary individual German seems to think they had any culpability. Is a greifer (a spy who turned Jews and other criminalized groups in to the Nazi's) guilty? Even if they are Jewish themselves? How about a scientist who collected statistics for the experiments conducted on unwilling human subjects in the camps? That is the moral part of the story. In addition, Geismar left behind in Berlin a married woman with whom he had an affair and wants to know if she is still alive. That's the love part of the story and in Kanon's hands these four threads of this book blend unselfconsciously. His prose is entertaining but not too brisk at the outset. He takes his time developing the stories and their actors. His dialogue is clipped, sparse, and believable, the moral and political ambiguities are neatly plotted and make good drama, the history is accurate and detailed, and he is good at suspense too. In the last 100 pages there is a terrific escape and chase scene - a real white-knuckler. This is a book that just screams movie - and evidently it was made into one, although I haven't seen it. Have any of you?

Good news! John Tierney has an article in today's Science Times on Matt Ridley's new book The Rational Optimist. Its thesis is that homo sapiens are unique not because of bigger brains, nor because of our ability to cooperate, but rather because we created ways to exchange goods and information.

Good news! John Tierney has an article in today's Science Times on Matt Ridley's new book The Rational Optimist. Its thesis is that homo sapiens are unique not because of bigger brains, nor because of our ability to cooperate, but rather because we created ways to exchange goods and information."The extraordinary promise of this event was that Adam potentially now had access to objects he did not know how to make or find; and so did Oz," Dr. Ridley writes. People traded good, services, and most important, knowledge, creating a collective intelligence..."This lead to circulating the knowledge of domesticating crops, the development of alphabets, and number systems and, Ridley argues, the creation of measured time, because the worth of a good or service was measured in how long a person would have to work to pay for it. One might also argue that it circulated small pox and MacDonald's but that isn't mentioned.

"The modern world is a history of ideas meeting, mixing, mating and mutating and the reason that economic growth has accelerated so in the past two centuries is down to the fact that ideas have been mixing more than ever before."His prediction is the spread of prosperity and happiness and the decrease of disease and violence. I will have to read the book to find out how he goes from point A to point B, and Tierney's piece certainly makes me want to, but I am not sure how mixing inevitably leads only to the progress of good things and the decrease of bad. One might argue that innovation is more likely to diffuse information, that is, that it will spread randomly until it becomes equally distributed. Is knowing more always better? The myth of Prometheus, pictured above, argued otherwise. What happens when bad things spread? The spread of what knowledge we have is inevitable, but is the eternal increase of knowledge inevitably positive? What happens the day that that knowledge includes the certainty of the destruction of our planet or the extinction of our species? But Ridley is a wonderful thinker and writer and amidst crashing markets, bombings, and the growth of the Tea Party, some unbridled optimism is welcome.

Reading in the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene is a readable account of how the reading brain works, as well as how it doesn't. Given the fact that printed text is a relatively recent human invention and, given the time scale of evolution, the brain could not have evolved specialized structures for reading per se but rather has adapted structures that evolved for more general visual purposes and applied them to this specialized task which combines seeing and recognizing objects and the reception of the abstract thoughts of another person. The form of letters have little to do with the meaning they ultimately communicate. As a result it has become the work of seven to ten of our earlier years to learn rote the relationship between our culture's symbols representing the units of sound (phonemes). These are combined into (words) from which we generate continuous phrases and sentences which accomplish the transfer of information and point of view. This is done at a minimum with some coherence, if not also some beauty, and the composer of those same units of meaning doesn't even have to be around to explain himself. It might seem roundabout that printed text has to take a two step journey from sound to meaning rather than going straight to meaning, but this is what allows language to communicate abstract thought:

Reading in the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene is a readable account of how the reading brain works, as well as how it doesn't. Given the fact that printed text is a relatively recent human invention and, given the time scale of evolution, the brain could not have evolved specialized structures for reading per se but rather has adapted structures that evolved for more general visual purposes and applied them to this specialized task which combines seeing and recognizing objects and the reception of the abstract thoughts of another person. The form of letters have little to do with the meaning they ultimately communicate. As a result it has become the work of seven to ten of our earlier years to learn rote the relationship between our culture's symbols representing the units of sound (phonemes). These are combined into (words) from which we generate continuous phrases and sentences which accomplish the transfer of information and point of view. This is done at a minimum with some coherence, if not also some beauty, and the composer of those same units of meaning doesn't even have to be around to explain himself. It might seem roundabout that printed text has to take a two step journey from sound to meaning rather than going straight to meaning, but this is what allows language to communicate abstract thought:I suspect that any radical reform whose aim would be to ensure a clear, one-to-one transcription of English speech would be bound to fail, because the role of spelling is not just to provide a faithful transcription of speech sounds. Voltaire was mistaken when he stated, elegantly but erroneously, that "writing is the painting of the voice: the more it bears a resemblance, the better." A written text is not a high-fidelity recording. Its goal is not to reproduce speech as we pronounce it, but rather to code it at a level abstract enough to allow the reader to quickly retrieve its meaning.The brain accomplishes this remarkable feat, Dehaene tells us (without even being there), via two pathways that operate simultaneously when reading is fluent. One path transfers the letter-string to it sound content (and the motor requirements of our making that sound with our vocal apparatus) prior to its meaning, and the other that goes for the identity of the word first and then the sound. A great number of pages in the book is spent on discussing the fruits of Dehaene and his colleague Laurent Cohen's labors identifying the left hemisphere's visual word-form area, a region of the brain whose purpose seems to be to be the visual analysis of the symbols that make up letters and words irrespective of their superficial differences. That is to say we can read word, WORD, or even WoRd equally easily and can tell the difference between ANGER and RANGE. You can see the visual word-form area in the picture representing the relative activity of regions of Dehaene's reading brain below, its the area right above his ear. There are other areas that accomplish the conversion of printed text into units of sound, still others that agree on the meaning of the assembly given not only its form but its context.

The typical right-handed person's brain has developed most of its key language processing areas in the left hemisphere (left handers are less reliable in this regard). This is true whether the personn reads from left to right or right to left and whether they read an alphabet whose symbols map to units of sound (as in these roman letters you are reading right now) or comprise pictures of whole words (as in logographic alphabets like Chinese). Dehaene, in fact, explores the evolution of different writing systems from pictoral markers in depth as he builds his case for how the human brain evolved the skill of reading, a section of the book I very much enjoyed.

The typical right-handed person's brain has developed most of its key language processing areas in the left hemisphere (left handers are less reliable in this regard). This is true whether the personn reads from left to right or right to left and whether they read an alphabet whose symbols map to units of sound (as in these roman letters you are reading right now) or comprise pictures of whole words (as in logographic alphabets like Chinese). Dehaene, in fact, explores the evolution of different writing systems from pictoral markers in depth as he builds his case for how the human brain evolved the skill of reading, a section of the book I very much enjoyed.We would not be able to read if our visual system did not spontaneously implement operations close to those indispensable for word recognition, and if it were not endowed with a small dose of plasticity that allows it to learn new shapes. During schooling, a part of this system rewires itself into a reasonably good device for invariant letter and word recognition.In the book's final chapter, Dehaene discusses cortical plasticity - a neuroscientific idea that is relatively recent and much in vogue. It is the ability of brain's neuron's to adapt their function from one purpose to another - for example, when a blind person's visual cortex cells become able to decode sensation of the fingertips to braille letters. Dehaene makes a case for the necessity of cortical plasticity in inventing cultural forms like number systems and the arts. It's one of those fun bits of reaching for the stars that a researcher has to save for when they write a book rather than a journal article. His voice comes off a little stuffy at times, but his theory is intricate - composed of many interleaving units - so his writing must be systematic in driving home each concept and then attaching is to its predecessor. His model for how the brain accomplishes reading, I must emphasize, is one of several, but he does acknowledge alternate viewpoints along the way. The lay reader may not find this book as accessible as Maryanne Wolf's Proust and the Squid, but it goes into more depth and synthesizes a lot of information into a coherent narrative arc. His diction is clear and the reading experience fluid and even entertaining. Dehaene's work is at the cutting edge of our understanding about the relationship between language and the brain so I found it a pleasure to get the story from one of its sources.

According to this view, our cortex is not a blank slate or a wax tablet that faithfully records any cultural invention, however arbitrary. Neither is it an inflexible organ that has somehow, over the course of evolution, dedicated a "module" to reading. A better metaphor would be to liken our visual cortex to a Lego construction set, with which a child can build the standard model shown on the box, but also tinker with a variety of other inventions.

My hypothesis disagrees with the "no constraints" approach so common in the social sciences, according to which the human brain is capable of absorbing any form of culture. The truth is that nature and culture entertain much more intricate relations. Our genome, which is the product of millions of years of evolutionary history, specifies a constrained, if partially modifiable cerebral architecture that imposes severe limits on what we can learn. New cultural inventions can only be acquired insofar as they fit the constraints of our brain architecture.

So … you’re halfway through a book and you’re hating it. It’s boring. It’s trite. It’s badly written. But … you’ve invested all this time to reading the first half. What do you do? Read the second half? Just to finish out the story? Find out what happens? Or, cut your losses and dump the second half.

If the book is trite, boring, and badly written I doubt I would have gotten half way (unless it's only 100 pages long - I'm willing to give most bad reading experiences 50 pages). There is no question for me on this point - dump it. What am I reading for? Fun, enlightenment, information - whatever the case - it's all for me. I have no obligation to anyone connected with my reading. Even if I have received the book for free to review I won't finish it (in fact, especially then, as I am trying to give an honest reaction to what I have read and it is usually something I would never have read in the first place). Who am I kidding? The author is not hanging around waiting for my opinion, ARCs are publicity, kids. I don't read for my many adoring fans, much as I love them both. Two exceptions - reading for school, I almost always complete assigned reading unless I am simply tortured by it, and reading something written by a friend, although my friends don't usually write things that are trite, boring, and badly written. They don't tend to sin in threes. Where I might sit on the fence is if a book has a dull subject but is brilliantly written (I almost never find this to be the case), or has a killer story but is written in illiterate fragments or a string of endless cliches. Even in these cases, I don't agonize over not finishing a book. Closing doors is healthy. There are enough choices to make in this information-saturated world and ruling one out lightens the burden. Lastly, although I sometimes talk about investing time, an economic metaphor in this case isn't entirely appropriate. If I have invested $1000 in a stock and it disappoints me by going down, to not sit it out means I have lost my money. Having spent a few hours in reading the first half of a book - if it was a good investment, then my time was not a wasted regardless of whether I continue or I stop. If it was obviously not a good investment from the get-go I shouldn't have read so far (and generally I don't). I may invest time to read, but it is only by continuing to invest it when I am getting nothing in return that I experience a loss. That is the reason I don't agonize about pulling out, there is only a cost for continuing. If a book is good enough to make me wonder whether, if I read on, it would improve then there is something compelling in it and I should consider the pleasure of that anticipation its own reward. Any way I look at it, reading is sheer indulgence and I'm going to trust my taste and follow my pleasure since I can't do that as relentlessly in most other areas of life. Anita Brookner's The Debut was her's in the fiction world (she had written art history prior to writing fiction); it was as well my first encounter with her writing, and I was pleasantly surprised. I had been led to expect the repressed work of a bookish spinster, but my experience of this novel about a young woman who has escaped into books to avoid the tyranny of her indulgent actress mother and clueless father, was of a literate mind which energetically subjugates words to its bidding to produce a wry, bittersweet story with acutely etched characters. Her's is a piquant voice, with a clearly defined moral stance, one whose observations are without mercy but also full of humor.

Anita Brookner's The Debut was her's in the fiction world (she had written art history prior to writing fiction); it was as well my first encounter with her writing, and I was pleasantly surprised. I had been led to expect the repressed work of a bookish spinster, but my experience of this novel about a young woman who has escaped into books to avoid the tyranny of her indulgent actress mother and clueless father, was of a literate mind which energetically subjugates words to its bidding to produce a wry, bittersweet story with acutely etched characters. Her's is a piquant voice, with a clearly defined moral stance, one whose observations are without mercy but also full of humor.Dr. Weiss, at forty, knew that her life had been ruined by literature.

In her thoughtful and academic way, she put it down to her faulty moral education, which dictated through the conflicting but in this one instance united agencies of her mother and father, that she ponder the careers of Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary, but that she emulate those of David Copperfield and Little Dorrit.

[...]

And yet she had known great terror, great emotion. She had been loved, principally b a leading philologist at the Sorbonne, but that was not her story. Her adventure, the one that was to change her life into literature, was not the stuff of gossip. It was, in fact, the stuff of literature itself. And the curious thing was the Dr. Weiss had never met anyone, man or woman, friend or colleague, who could stand literature when not on the page.

... The taxi had unloaded George and Helen into a maelstrom of returning holiday makers, a world they did not know existed: Elderly men with veins standing out on their foreheads trying to cope with five suitcases, elderly women with swollen feet and glistening white cardigans bought especially for the holiday, enduing the fright of a lifetime in order to enjoy the pleasure they had promised themselves all through the winter, too many children, shrill with tiredness, their long hair sticking to their damp faces, their mouths smeared and stained with sweets and ice lollies, none of them aspiring even to the relative comfort of a taxi, but queuing patiently for buses, shifting their burdens from hand to hand, trying to quiet the children, longing for that cup of tea at home, safe at last for another year.Doesn't that paragraph makes you feel sticky with the grime of a long journey? Brookner's writing can appreciated for its precision, its delicious topography, its consistency of outlook, and its ability to call up visceral experience. There is another similarly potent paragraph on caring for an elderly invalid that is a gem.

In anticipation of writing about Anita Brookner's precisely observed, and sardonic The Debut in the coming days, here is a Paris Review interview with her from 1987. Very exacting in her moral outlook and somewhat rigid in her thinking, she started writing novels in her 50s and has produced one per year. This is the first of her's I have read. Great writing - a potent voice that envelops one in the world of her characters. It is fascinating, as always, to read of her process and her influences.

In anticipation of writing about Anita Brookner's precisely observed, and sardonic The Debut in the coming days, here is a Paris Review interview with her from 1987. Very exacting in her moral outlook and somewhat rigid in her thinking, she started writing novels in her 50s and has produced one per year. This is the first of her's I have read. Great writing - a potent voice that envelops one in the world of her characters. It is fascinating, as always, to read of her process and her influences.

Bernard MacLaverty's Cal - 150 pages that are as densely packed with passion and tension as any I've read in Dostoyevsky or Hardy. The 19-year-old title character lives in Northern Ireland. A Roman Catholic, he is hounded and physically attacked by the Protestant Orangemen. His friends have joined the IRA in response to the violence with which they are threatened. Cal finds the violence too much for him. The struggles of nations would not be important if they didn't effect the lives of individual people. This book is about the converging of conflicts political and personal - the political and religious struggles of an oppressed people, a first great passionate love, and the dilemmas of a sensitive and thoughtful teenager as he makes the moral choices that are going to shape his whole life. I felt deeply the greatness of these struggles as I read. Read my full rave here.

Bernard MacLaverty's Cal - 150 pages that are as densely packed with passion and tension as any I've read in Dostoyevsky or Hardy. The 19-year-old title character lives in Northern Ireland. A Roman Catholic, he is hounded and physically attacked by the Protestant Orangemen. His friends have joined the IRA in response to the violence with which they are threatened. Cal finds the violence too much for him. The struggles of nations would not be important if they didn't effect the lives of individual people. This book is about the converging of conflicts political and personal - the political and religious struggles of an oppressed people, a first great passionate love, and the dilemmas of a sensitive and thoughtful teenager as he makes the moral choices that are going to shape his whole life. I felt deeply the greatness of these struggles as I read. Read my full rave here. This book has everything - love, suspense, moral conflict, social criticism, psychological acuity, and crack writing. It is pitch-perfect on the a fast-paced, ostentatious, brutal beauty of Rome. Lambert's writing is rich with observations both interior and exterior that imbue character and place with clarity and instantaneous complexity. This novel, though entertaining to read, is an unambiguous critique of the moral hypocrisy that infects the powerful and the nature of crime which combines an abuse of power with the dehumanization of innocent people. Read my full rave here.

This book has everything - love, suspense, moral conflict, social criticism, psychological acuity, and crack writing. It is pitch-perfect on the a fast-paced, ostentatious, brutal beauty of Rome. Lambert's writing is rich with observations both interior and exterior that imbue character and place with clarity and instantaneous complexity. This novel, though entertaining to read, is an unambiguous critique of the moral hypocrisy that infects the powerful and the nature of crime which combines an abuse of power with the dehumanization of innocent people. Read my full rave here. Molly Fox is a celebrated actress - a woman who delves deep into what makes up a 'self.' It is her profession to create characters from that knowledge through the medium of her self. Yet, when it comes to letting others truly know her, she does not. 'Can we ever know another?', this novel asks. The Irish novelist Deirdre Madden fashions a deep and beautiful book on this potentially abstract musing that is redolent with the pain of the distance we have from all others - even those we love most - and simultaneously rich with the rewards of the communion we can make through long acquaintance. She is particularly good at using the processes of the actor and writer to reflect on the ways we can inhabit the inherent contradiction of knowing another, but the mechanisms are so integrated with the events of this narrative that it is difficult to reveal them without ruining your reading of this book. This book is a powerful work of art with an undisturbable sense of wholeness. Read my full rave here.

Molly Fox is a celebrated actress - a woman who delves deep into what makes up a 'self.' It is her profession to create characters from that knowledge through the medium of her self. Yet, when it comes to letting others truly know her, she does not. 'Can we ever know another?', this novel asks. The Irish novelist Deirdre Madden fashions a deep and beautiful book on this potentially abstract musing that is redolent with the pain of the distance we have from all others - even those we love most - and simultaneously rich with the rewards of the communion we can make through long acquaintance. She is particularly good at using the processes of the actor and writer to reflect on the ways we can inhabit the inherent contradiction of knowing another, but the mechanisms are so integrated with the events of this narrative that it is difficult to reveal them without ruining your reading of this book. This book is a powerful work of art with an undisturbable sense of wholeness. Read my full rave here. The struggle to keep the champagne bubbling when it's gone flat is the action filling Evelyn Waugh's 1930 satire Vile Bodies. Stephen Fry's brilliant film adaptation, Bright Young Things released in 2003 captures the feel of a breathless, manic party. Jim Broadbent, Stockard Channing, Peter O'Toole, Simon Callow, Stephen Campbell Moore, Emily Mortimer, James Mcavoy, Imelda Stuanton, and Fenella Woolgar are some of the beautifully cast actors who maintain an understated hysteria, if you can imagine understated hysteria. The love that director and cast have for these characters is what impresses me the most. It would be so easy to show us how vile these people are - how silly, how louche, how fey - but instead they love them to death. Raveworthy. Read my full rave here.

The struggle to keep the champagne bubbling when it's gone flat is the action filling Evelyn Waugh's 1930 satire Vile Bodies. Stephen Fry's brilliant film adaptation, Bright Young Things released in 2003 captures the feel of a breathless, manic party. Jim Broadbent, Stockard Channing, Peter O'Toole, Simon Callow, Stephen Campbell Moore, Emily Mortimer, James Mcavoy, Imelda Stuanton, and Fenella Woolgar are some of the beautifully cast actors who maintain an understated hysteria, if you can imagine understated hysteria. The love that director and cast have for these characters is what impresses me the most. It would be so easy to show us how vile these people are - how silly, how louche, how fey - but instead they love them to death. Raveworthy. Read my full rave here. Tell Me Everything by Sarah Salway . I opened this book last night and didn't stop reading it until I had finished it. The nearest voice I can think to compare Sarah Salway's to is Lorrie Moore's, and coming from me that is a big compliment. In it Molly experiences a few breaches of trust as a young woman that leave her seriously wounded. She closes down and protects herself by eating. When we meet her she has become one of life's castaways, seriously overweight without a job, a home, or any sense of herself. She meets five people - Mr. Roberts who gives her a job, Mrs. Roberts, Tim - a man of mystery, Liz - a librarian who recommends French authors, and Miranda, a hairdresser. With these relationships she begins to reclaim herself. The story is full of perfectly wrought descriptions, complex observations of human pain and fantasy, and cogent storytelling. Read my full rave here.

Tell Me Everything by Sarah Salway . I opened this book last night and didn't stop reading it until I had finished it. The nearest voice I can think to compare Sarah Salway's to is Lorrie Moore's, and coming from me that is a big compliment. In it Molly experiences a few breaches of trust as a young woman that leave her seriously wounded. She closes down and protects herself by eating. When we meet her she has become one of life's castaways, seriously overweight without a job, a home, or any sense of herself. She meets five people - Mr. Roberts who gives her a job, Mrs. Roberts, Tim - a man of mystery, Liz - a librarian who recommends French authors, and Miranda, a hairdresser. With these relationships she begins to reclaim herself. The story is full of perfectly wrought descriptions, complex observations of human pain and fantasy, and cogent storytelling. Read my full rave here.