Award-winning Canadian novelist Marina Endicott is not widely known in the U.S., but she deserves to be. Her The Little Shadows (Doubleday Canada, 2011) is an entertaining, coming-of-age saga of three sisters, Aurora, Clover, and Bella, working for their supper on the vaudeville circuit circa 1912 with their widowed mother. Aside from simply being a good story, there were three things I particularly enjoyed about The Little Shadows.

This is a coming-of-age story about women rather than men, which is still a literary rarity. When it begins, the emphasis is on the sisters' act, how they function as one, as their survival depends upon its success. But as they mature, they become individuals as artists and women. The joy of the plot is tracing the development of their characters and how their talents shape them to be the women they become.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Saturday, December 12, 2015

A tale of coming together while coming apart (Books - Sleeping on Jupiter by Anuradha Roy)

In Sleeping on Jupiter (2015, Hachette India) Anuradha Roy creates a tale of convergences. An Indian girl, Nomi, is orphaned when her parents are slaughtered in war. She is given refuge in an ashram, where she is sexually abused by the guru, after which she is adopted by a European woman and raised in Scandanavia. As a young woman she returns to India, to Jarmuli, the seaside town where the Ashram was located. Three older women, good friends, go on a long-planned trip to the same seaside town - a well-earned but final fun weekend, as one of them is becoming infirm. They make a pilgrimage to Jarmuli's famous temple. At the same time, one of the older women's sons has also made his way to Jarmuli for work, following the break-up of his marriage. And a young man tries to earn enough money to escape from under the abusive thumb of his uncle by working as a temple guide. These characters come to Jarmuli, some from darkness in their past, some with present woes. Their meeting is meant to have a redemptive ring to it, but Roy's beautiful lyrical prose doesn't seem to raise the convergence above coincidence.

Saturday, November 28, 2015

Life is more than what we know (Books - In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman)

A well-to-do Londoner, his marriage and his job as an investment banker in ruins as the economy collapses in 2008, receives a visit. Zafar, whom he knew in college, is of Bangladeshi birth, an orphan, a mathematical prodigy, an Oxford graduate, and a human rights lawyer. Agitated, traveling only with a backpack, Zafar arrives at our narrator's home and tells the remarkable story of how he came to be as he is now - a tale of contemporary Asian politics, English colonialism, and the Incompleteness Theorem of mathematician Kurt Godel.

In In the Light of What we Know by Zia Haider Rahman (Picador, 2014) story- telling itself is an important part of the story. Both who we are and how we're known, it explains, are narrative constructions.

In In the Light of What we Know by Zia Haider Rahman (Picador, 2014) story- telling itself is an important part of the story. Both who we are and how we're known, it explains, are narrative constructions.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

The Man Who Wouldn't Be Known (Books - A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara)

Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life (Doubleday, 2015) has been written about widely and short-listed for the 2015 Man Booker Prize. As I started it on the recommendation of my local bookseller this past summer, I had heard very little of the hooplah. I believed I was reading a typical modern tale of four friends who went to college together, chronicling their coming of age, their successes, failures and jealousies in relationships and work. But A Little Life defies this genre. The friends are an architect, an actor, an artist, and their friend Jude, around whom they and this story revolve. Jude is a man of great beauty, although he is never physically described by the author. He is brilliant and creative, although he makes his very ample living as an attorney. Yet with all of the accoutrements of success, Jude cannot allow himself be loved, so severely is he traumatized by abuse he suffered as a child.

Sunday, November 1, 2015

Revolution in thought and practice (Books - The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow)

Erasmus Darwin, 18th Century physician, writer, grandfather of the more famous Charles, and one of the eponymous lunar men of Jenny Uglow's book, wrote in the later years of his life:

Credulitas. Credulity. Life is short, opportunities of knowing rare; our senses are fallacious, our reasonings uncertain; man therefore struggles with perpetual error from cradle to the coffin. He is necessitated to correct experiment by analogy, and analogy by experiment...If you live life with an ounce of curiosity in you, you likely recognize the longing Darwin so pithily expressed . If you, like Darwin, James Watt and Matthew Boulton inventors of the steam engine, Josiah Wedgwood potter and chemist, Joseph Priestley religious radical and the discoverer of oxygen, or any of the other principal characters in Uglow's The Lunar Men (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002), live to pursue your curiosities, then this is your creed.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

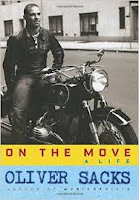

Two memoirists of passion (Books - Love is Where it Falls by Simon Callow & On the Move by Oliver Sacks)

In the last several months I read the memoirs of two fascinating, beloved, gay, British-born public figures. One was published recently, the other 15 years ago. One works in one of my areas of expertise - the arts - and the other in the other - the science of the brain. The authors were actor Simon Callow and Dr. Oliver Sacks. Their books are Love is Where it Falls (Penguin Books, 2000) and On the Move: A Life (Knopf, 2015). Their books are forthright and generous, the authors deeply giving of themselves, and they are crack writers. Knowing them now, as I do, it is fitting that these copies are signed.

Oliver Sacks has written so humanely and observantly of his patients' lives (for instance here and here), and so openly of his peculiar fascinations, that this memoir, and this is the third of his books that might be classified as such, was a welcome departure. Here, finally, Sacks scrutinized as deeply and wrote as openly about his own life - particularly his inner life. This was welcome not only in knowing more about so great a man and storyteller, but also because one read it in the context of his impending death (about which he wrote so beautifully here and here) and because one could feel in the narrative drive this desire to share it all before it was too late.

Early in Sacks's writing career, the great poet W. H. Auden said to Sacks

She had, she said, been walking down Piccadilly, musing on the fact that it was Moliere's birthday and that not a single actor in England would know, much less care. Musing on this sad reality, it had suddenly struck her that, yes, there was an actor in England who would know and care: me. And so she had gone into Fortnum's and ordered the wine and had it sent to me, to celebrate, with my actor friends, the great playwright's birthday.So begins an unlikely romance between a fierce, 70-year old theatrical literary agent, Peggy Ramsay, and 30-year-old actor Simon Callow. I find myself wanting less to write about the merits of this book than to quote from it. These two live passionately and are attracted to each other so relentlessly, because their taste in art is not so much an aesthetic about life's decor as a deeply held principle about the way to live it.

We must feel, that is everything. We must feel as a brute beast, filled with nerves, feels, and knows that it has felt, and knows that each feeling shakes it like an earthquake.or

I do so passionately believe that the only meaning of life is life, that to live is the deepest obligation we have, and that to help other people live is the greatest achievement. It's in that light that I see acting, and that alone.

Oliver Sacks has written so humanely and observantly of his patients' lives (for instance here and here), and so openly of his peculiar fascinations, that this memoir, and this is the third of his books that might be classified as such, was a welcome departure. Here, finally, Sacks scrutinized as deeply and wrote as openly about his own life - particularly his inner life. This was welcome not only in knowing more about so great a man and storyteller, but also because one read it in the context of his impending death (about which he wrote so beautifully here and here) and because one could feel in the narrative drive this desire to share it all before it was too late.

Early in Sacks's writing career, the great poet W. H. Auden said to Sacks

You're going to have to go beyond the clinical... Be metaphorical, be mystical, be whatever you need.This is really where Sacks's writing succeeds so magnificently in combining what is true with what feels true in a story. I cherish his writing and hope to celebrate his life in a live program in the coming year.

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Impressions of Napoli and Ferrara (Books - Neopolitan Novels by Elena Ferrante & How to Be Both by Ali Smith)

Elena Ferrante's Neopolitan quartet, composed of My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, and, The Story of the Lost Child, is a stunning portrait of the friendship between two women and particularly how the life of a great friend can become subsumed in one's own. It is a literary page-turner and arriving at the end of some 1,700 pages I experienced how masterfully structured it was. Ferrante's narrator is herself a writer and the quartet, especially the final volume, reflects on the process and consequences of writing. She manages to be smartly self-aware without becoming overly explanatory. Her mastery of craft is made plain to me when I think of the broad cast of some 40 characters with whom I had become familiar. The scene writing, as in the wedding reception that closes the first volume, brings the huge cast into spectacularly vivid focus, even while creating a tone that feels so of its period (late 50s/early 60s) that my mind's eye sees it in the Technicolor palate. I cannot recommend these enough.

I feared that Ali Smith's How to be Both might become twee because of its concept, but I should have known better. Smith has constructed a pair of interrelated tales, one set in renaissance Italy based on the life of fresco painter Francesco del Cossa and the other set in modern day Britain concerning a daughter mourning the death of her mother, an activist. The plots are cleverly referential of one another but don't yield their secrets easily. The concept, such as it is: these stories can be read with either as the first. In the order I read them (15th century first) the narrative keeps the reader working to understand what Smith's narrator sees. Without giving away too much, she/he sees aspects of the other narrative. In fact, each story's art making protagonist has a window into the other, and the effect for the reader is something like an infinity mirror. Smith's literary time travel is a puzzle of sorts, offering some intellectual smiles and even thrills at hearing the 'click' as a detail falls into place. I am a rabid fan of Smith's Artful and her themes of identity, loss, and the uses of art are visited here again but in a different guise. Smith loves to play with form, and to let you know it. If Artful was an argument (a narrative about the composition of a lecture on art), How to be Both is a more traditional immersive narrative experience, but one that plays with the tension between then and now, between life and death, between art and audience, and between visual and narrative form. You know those 'which writer would you invite to lunch questions?' Ali Smith would be one of my guests.

I feared that Ali Smith's How to be Both might become twee because of its concept, but I should have known better. Smith has constructed a pair of interrelated tales, one set in renaissance Italy based on the life of fresco painter Francesco del Cossa and the other set in modern day Britain concerning a daughter mourning the death of her mother, an activist. The plots are cleverly referential of one another but don't yield their secrets easily. The concept, such as it is: these stories can be read with either as the first. In the order I read them (15th century first) the narrative keeps the reader working to understand what Smith's narrator sees. Without giving away too much, she/he sees aspects of the other narrative. In fact, each story's art making protagonist has a window into the other, and the effect for the reader is something like an infinity mirror. Smith's literary time travel is a puzzle of sorts, offering some intellectual smiles and even thrills at hearing the 'click' as a detail falls into place. I am a rabid fan of Smith's Artful and her themes of identity, loss, and the uses of art are visited here again but in a different guise. Smith loves to play with form, and to let you know it. If Artful was an argument (a narrative about the composition of a lecture on art), How to be Both is a more traditional immersive narrative experience, but one that plays with the tension between then and now, between life and death, between art and audience, and between visual and narrative form. You know those 'which writer would you invite to lunch questions?' Ali Smith would be one of my guests. Still to come, capsules of Simon Callows' Love is Where it Falls, Olver Sacks's On the Move, and Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life and while-I-read impressions of Hiding in Plain Sight and Lunar Men.

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

David Grossman on his Writing Process

If you have loved David Grossman's fiction, as I have (see here on To the End of the Land), then you will appreciate this 2007 Paris Review interview with him on Arabs and Israelis, his writing process, and his life.

In recent years, I feel I’m less and less influenced by writers. I do not see this as a good sign, by the way. I want to be influenced by writers. I think it is a sign of being open...

...the books that really matter, the books that I cannot imagine my life without having written, are the more demanding ones, like The Book of Intimate Grammar, Be My Knife, See Under: Love, and the book I’m writing now. I may occasionally like to write an entertaining book, but I take literature seriously. You’re dealing with explosives. You can change a reader’s life, and you can change—you should change, I think—your own life.

Usually a lighter book will serve as a kind of recovery for me. I devastate myself when I write a certain kind of book—there is a process of dismantling my personality. All my defense mechanisms, everything settled and functioning, all the things concealed in life break into pieces, because I need to go to the place within me that is cracked, that is fragile, that is not taken for granted. I come out of these books devastated. I don’t complain, of course. This is how books should be written. But my way to recover from this sense of total solitude is to write books that will bring me into close contact with other people. I wrote The Zigzag Kid because I had to recover from The Book of Intimate Grammar and Sleeping on a Wire.

Saturday, May 23, 2015

Past inhabits present in the lives of 3 families (Books - The Turner House by Angela Flournoy; A Legacy by Sybille Bedford; & Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz)

Three family sagas are the subject of this post. What I like about this form is the intertwining of the characters' narratives with a sense of place and time. When it works well, I experience both the familiarity of people wanting, thinking and behaving, and the distance of an unfamiliar time and which gradually lessens, becoming more and more like my own. Sybille Bedford's A Legacy (Counterpoint, 1956, 1999) set in late 19th and early 20th century Germany, Naguib Mahfouz's Palace Walk (Doubleday, 1956, 1990) set in early 20th century Cairo, and Angela Flournoy's accomplished debut The Turner House, (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015) set in past and present day Detroit.

Saturday, May 16, 2015

Two formative men of the American Theatre (Books - A Life by Elia Kazan & Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh by John Lahr)

The life stories of two American Theatre makers monopolized my reading back in January: Elia Kazan: A Life, film and theatre director Kazan's hefty, probing memoir (Alfred A. Knopf, 1988) and Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (W.W. Norton & Co. 2014), John Lahr's deftly paced, thoroughly researched, deeply perceptive biography of the great playwright. Two men could not have had a greater influence on the structure and build of action, the feeling of innocence and epiphany, the rhapsodic music of text, the themes of individuality and of sex that were the coming-of-age of the American theatre and film in the 1930s - 1970s, than Williams and Kazan. Two men could not have been more superficially different - Kazan was the son of Greek immigrants, born in Turkey, a scrappy fighter, and relentless womanizer, Williams a grandson of an American preacher, delicate, gay, a virgin until twenty-six years of age - but fundamentally they were remarkably similar. Aside from their obvious love of theatre, both seemed dissatisfied with the restrictions of their world, were driven to create theatre to give veiled expression to a deep sense of personal failure, both felt outsiders and compulsively pursued relief in work or, failing that, one from drink and the other from sex. John Lahr's quotes a letter from Williams to Kazan:

The life stories of two American Theatre makers monopolized my reading back in January: Elia Kazan: A Life, film and theatre director Kazan's hefty, probing memoir (Alfred A. Knopf, 1988) and Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (W.W. Norton & Co. 2014), John Lahr's deftly paced, thoroughly researched, deeply perceptive biography of the great playwright. Two men could not have had a greater influence on the structure and build of action, the feeling of innocence and epiphany, the rhapsodic music of text, the themes of individuality and of sex that were the coming-of-age of the American theatre and film in the 1930s - 1970s, than Williams and Kazan. Two men could not have been more superficially different - Kazan was the son of Greek immigrants, born in Turkey, a scrappy fighter, and relentless womanizer, Williams a grandson of an American preacher, delicate, gay, a virgin until twenty-six years of age - but fundamentally they were remarkably similar. Aside from their obvious love of theatre, both seemed dissatisfied with the restrictions of their world, were driven to create theatre to give veiled expression to a deep sense of personal failure, both felt outsiders and compulsively pursued relief in work or, failing that, one from drink and the other from sex. John Lahr's quotes a letter from Williams to Kazan:Friday, March 20, 2015

3-D tour through brain space for Brain Awareness Week

I talked to curious students about the Brain at BiobBase yesterday and took a really amazing tour through a 3-D brain in a planetarium...no, really. Check out my Brain Awareness Week blog by clicking here and scrolling down.

Thursday, March 12, 2015

Improvisation in the Sciences - improvisations on a panel discussion for Brain Awareness Week 2015)

| ||||

When I heard that the opening event of Brain Awareness Week this year was on the theme of improvisation and involved arts and science, I knew that I wanted to be the one to report on it. I decided to do this blog as an improvisation; that is what follows.

Improvisation 1

I am riding the subway on my way to Improvisation in the Sciences at Columbia. It’s the first event of Brain Awareness Week and involves musicians and scientists. Given the theme, and since I am both an artist and neuroscientist, I decided to improvise this blog, a little experiment. I’m feeling a bit nervous, like I’m performing myself. Before I left my apartment, I sat down to play a sonata on the piano, I thought it would get me in the mood but I was interrupted by a phone call letting me know that the subways were delayed. I ran out of the house. Having stopped the sonata in the middle, the strains are repeating unresolved in my mind’s ear. I am anticipating music on the program, but it probably won’t be this kind of music.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

Whimsy in the face of chaos as Russian history repeats itself (Books & Opera - The Spectre of Alexander Wolf by Gaito Gazdanov, There Once Lived a Mother.... by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk by Dmitri Shotakovch)

Today, as more than 50,000 Russians march to honor Boris Y. Nemtsov, the Putin critic who was assassinated a few days ago, it seems timely to consider some of the art made in the context of Soviet and Russian regimes, which may be different for the name they give their ruler but seem alike in their repression of opposing views. While Putin is stripping off his

shirt and getting into bed with the oligarchs, politically repressing

homosexuals, and annexing Crimea as the Empress Catherine the Great did before him, I read The Spectre of Alexander Wolf, written by Gaito Gazdanov, a Russian living in Paris in the late 1940s, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's There Once Live a Mother Who Loved her Children, Until They Moved Back In, three novellas about Soviet Life written between 1988 and 2002, and I saw the 1934 Shotakovich opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk at the Metropolitan Opera.

These three works plumb life's extremities, attempting the creation of some kind of meaning in the face of the suffering endured by the artist. So we can thank repressive regimes for that literary construct we call the Russian soul. Each of these works express deep longing for something better.

These three works plumb life's extremities, attempting the creation of some kind of meaning in the face of the suffering endured by the artist. So we can thank repressive regimes for that literary construct we call the Russian soul. Each of these works express deep longing for something better.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)