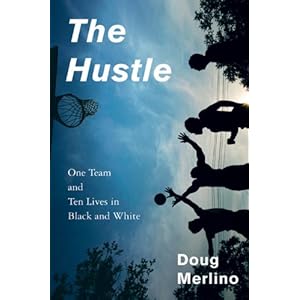

The Hustle by Doug Merlino is about the socio-politics, economics, and personal drama of relations between blacks and whites in America. Merlino, a journalist, (and also a friend and the provider of this advance copy) played on a basketball team in 1980s Seattle that was the dream- child of a black coach from the inner-city and a wealthy white entrepreneur. Both were fathers of teenage boys, both were proponents of the value of team sports for making men out of boys who can collaborate with one another on reaching a collective goal, but both wanted an experience for the boys of their city that was about building a less racially divided future. When Merlino learns of the death of one of his fellow teammates, he is moved to remember:

The Hustle by Doug Merlino is about the socio-politics, economics, and personal drama of relations between blacks and whites in America. Merlino, a journalist, (and also a friend and the provider of this advance copy) played on a basketball team in 1980s Seattle that was the dream- child of a black coach from the inner-city and a wealthy white entrepreneur. Both were fathers of teenage boys, both were proponents of the value of team sports for making men out of boys who can collaborate with one another on reaching a collective goal, but both wanted an experience for the boys of their city that was about building a less racially divided future. When Merlino learns of the death of one of his fellow teammates, he is moved to remember:Reading the story again, it becomes clear that the reason Tyrell's death was considered worthy of the front page was his involvement in integration programs - there was one where wealthy families from the suburbs "adopted" poorer ones at holiday times; and there was our team. The reported spoke to Coach McClain, who told her, "We thought it was a good idea to expose these different kids to each other, to combine inner-city kids with rich white kids. And it worked."The basketball team was, in essence, a social experiment in knowing the other. Merlino fulfills that experiment in writing a book that attempts to understand whether they gained that knowledge and the men that the team members became as a consequence of it.

I wonder if it had actually "worked" for anyone. Did any of the white kids still think about it? What had happened to my black teammates who'd gotten into private schools through Randy Finley's efforts? It was nearly twenty years since we'd all practiced together in the Lakeside gym. How had my teammates fared? What kind of men were they? Did anyone, like me, miss the amaraderie we got from playing together?

He takes on two roles in this book, one as a team-member who was affected by the experience, and who is touched as he gets to know each of his fellow team members as adults:

We pull up the driveway in front of my house, a large, gray, modernist structure with two gables. It has a basketball hoop and the outline of a key set in front of the three-car garage. Damian asks, "What side do you live on?"This is a personal, retrospective voice, one of memory. This is the less formal of the two. Merlino peppers his memoir with relaxed, chatty, diction:

"What do you mean?"

"Do you live on the right side or the left side?"

It takes me a second to catch on.

"It's just one house," I say, clutching my gym bag.

"You mean this is just for your family?"

"Yeah, we're the only ones who live here."

I pull the door open and thank Coach McClain for the ride.

"I'll see you guys at practice," I say and scurry into the house.

I'm embarrassed. All the gawking undermines the feeling fostered by playing on the team - that we are all equals. I worry that my teammates might not like me after seeing the house. The next day at school, Eric tells me that the guys had joked about my reaction on the way back to the Central Area, saying "He probably didn't invite us in because he was scared we'd steal everything."

[...]

There is nothing I can really say. I have never seen house and have no idea how he lives. For the whole season, the black side of the team always makes the commute north. We never visit the Central Area.

On the court, though, the team kind of resembles the chickens - they get blown out in the three games they play.Although full of perceptive details, the frequent use of phrases more typical of spoken diction, gives some of these passages an equivocal tone. This creates a modest character for Merlino the team member, one that is easy to read. It sometimes feels a less secure voice which can undermine his security as the chronicler of his teammates' personal narratives, but the positive side of that choice is that it communicates the unease of race as a subject that is so prevalent in America out of which Merlino writes. He writes these sections in the present tense which gives them immediacy:

JT joins the freshman basketball team and scrapes by in school. Then his mom, who has always been the center of his life, starts to use cocaine, and things quickly go south from there. Often when JT comes home, the shakes are drawn and all the lights are off. There's no food in the house. People stop by at all hours, laughing and talking while JT tries to sleep. One guy passes out in the living room with a stack of money piled on his belly. JT stops going to school, runs away from home, and takes to the streets, sleeping in bus shelters when he can't find any other place. He never plays organized basketball again.This is, I acknowledge, a contemporarily accepted literary practice, but I sometimes found it jarring, so aware was I of the key function that memory was playing. I thought that the distance afforded by past tense might have been able to be more consistently played off of the writer's present knowledge. Granted, the use of present tense probably makes for a less choppy narrative.

Merlino's second role assumes a distinct narrative voice from the first. It is that of the journalist who gives us context - the social history of black Seattle, the economics of cocaine use in American cities, Seattle's tech boom and subsequent bust - and then brings it back to the story.

...On the West Coast, cocaine was brought up through Mexico and smuggled over the border, where it was then sold to already established street gangs in Los Angeles. They converted the powder to crack and began to sell it in their territories, with violence often erupting when one set infringed on the turf of another.or

With their own markets saturated, the Los Angeles gangs began moving the drug to other cities, which was as simple as loading the trunk and heading up the freeway....The first time crack really registered in my consciousness came that March, when a different issue of Newsweek landed in our mailbox. The headline KIDS AND COCAINE was splashed on the front...

For middle-class people, this had been the model for decades - men went off to the office or factory, worked as part of a team within a formalized structure (the corporation or the state), played their part, and came home to the women and children. This had been the pattern since industrialization in the mid- and late 1800s, when youth sports leagues such as the YMCA and the AAU had been established. With men leaving farms to work in offices and factories, the idea of Muscular Christianity was that boys needed organized structures in which they could develop physically and enter into competition to avoid becoming too feminized. The skills learned on the field - stamina, discipline, sacrificing for the good of the team - were supposed to translate later into success in the working world. This was still the model when we were boys...These passages are terse, energetic, and fact-filled. They provide context that is relevant to the story and efficiently tied it back to the personal narratives, and in contrast to the voice assumed in the personal narratives, this one projects confidence.

The Hustle brings together these two perspectives in one book that has value because it treats the sociopolitical history of race credibly while communicating its relevance to individual's lives. Race as it is dealt with in America today, is a subject that makes many non-American roll their eyes, but it is relevant to struggles in other countries that one can read in the papers every day: the Turkish workers in Germany, the North Africans in Holland, the Pakistanis in England. These have socio-economic and imperialist roots without the added burden of legalized slavery, but their relevance is still apparent. Race is a subject many Americans probably hoped they had gotten beyond by electing a Black president, but it is ubiquitous and, at this point in our history largely inseparable from socioeconomic inequity. The Hustle is an accessible source of insight. While it is useful to know facts about social, political and economic history of the relations between blacks and white in America, that can be comfortably distancing. At the end of the day its meaning is most apparent in its consequence to individual lives. The Hustle succeeds as a book by being honest about what's personal, clear-eyed about what is factual, and having its narrative driven by the emotions of nostalgia and loss. It is to be released in December but you can pre-order a copy here.

No comments:

Post a Comment