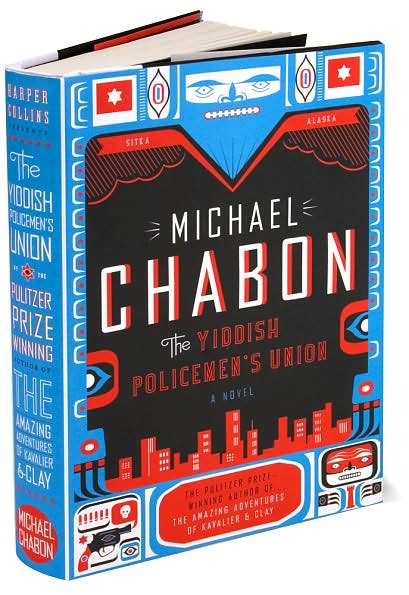

Grandma's soup is no longer the only place I can put the words "hard boiled" with the words "matzoh ball." Michael Chabon has written a noirish mystery, post-divorce love story, comdey, historical revisionist uh...thing called The Yiddish Policemen's Union. It's set in Sitka, a safe haven for the Jewish people established by the American government in Alaska after the 1940s collapse of an attempted Israeli state. On the eve of the reversion of this federal district to Alaskan native jurisdiction, detective Meyer Landsman discovers the corpse of a former chess prodigy turned heroin addict in the seedy hotel where he himself lives. This is noir so, of course, he is drinking relentlessly, following the dissolution of his marriage. His partner is half-Tlingit and half-Jewish, his boss is his ex-wife, and the murder victim turns out to be... well, I won't spoil it. And Chabon chose the word "amazing" for the title of his last best seller!?!

This is a fun book to read. It's 400 pages, fast-moving and funny. Chabon mines the incongruous marriage of noir, Alaska, and Yiddish-speaking Jewish culture for every comic possibility and he does create characters I cared about - Landsman, his partner, and the murder victim are all complexly fashioned portraits of people with compelling internal conflicts - they're not merely odd combinations for the sake of the maximum number of laughs. However, finally the novel does so many different things -noir, comedy, historical revisionism - it didn't satisfy me equally with all of them.

It offers historical revisionism. This was interesting in one way - it draws parallels to the complications of the current Israeli state, also an imperfectly created secular safe haven for Jews following the Holocaust, it too appropriated an isolated territory, it too created provision for reversion of some land for the use by its "natives" the Palestinians (both Israel and Jordan were to have done this but neither made good on it). It, like the book, features crazy bands of Orthodox radicals who have other plans. Chabon's Sitka sets the story in Alaska, which is so incongruous it's funny - but the issues are similar and so it holds the story at an arms distance and lets us look at the Israeli/Palestinian mess separately from the issue of a "holy" land. As such the revisionism seemed to me to have a point other than comedy. However, I thought it actually lacked imagination in being too narrowly focused. Since Chabon created an alternative reality (the way Phillip K. Dick does in The Man in the High Castle - a book set in a universe where the other side won World War II ), and yet it seems as though only this has changed. Cars are still called by the same brand names, the American president, though unnamed, seems awfully familiar. It bothered me that although this rather important historical fact changed, the world seemed the same in all other ways. It made this alternative reality too convenient and, therefore less plausible.

He does really have fun with some linguistic possibilities since, in this Jewish district the everyday language is Yiddish - a hybrid language. So when one character outside the culture learns Yiddish from a German professor in college he is said to speak it "like a sausage recipe with footnotes."

Chabon can be a very funny writer and he certainly piles on the indignities for Landsman who like most noir detectives is airsick, pistol whipped, imprisoned, and survives on no food and alcohol for four days. But sometimes Chabon didn't seem to know when to stop there is a point when Landsman loses most of his clothes (we're in Alaska) when he resembled the principal in the film Ferris Bueller's Day Off (if that is a meaningful parallel - or maybe think of Cary Grant toward the end of Bringing up Baby). The indignities are taken so far, they derail the noir and become farce and that removed me from the spell of the story. This compromised the mystery angle of the story and, therefore, the suspense.

There is plenty of juicy writing, on the other hand, that did nothing to hinder and everything to help my enjoyment of the story. For example:

He stands by the window, watching the sky that is like a mosaic pieced together from the broken shards of a thousand mirrors, each one tinted a different shade of gray. The winter sky of southeastern Alaska is a Talmud of gray, an inexhaustible commentary on a Torah of rain clouds and dying light. Uncle Hertz has always been the most competent, self-assured man Landsman knows, neat as an origami airplane, a quick paper needle folded with precision, impervious to turbulence. Accurate, methodical, dispassionate.. There were always hints of shadow, or irrationality and violence, but they were contained behind the wall of Hertz's mysterious Indian adventures, hidden on the far side of the Line, covered over by him with the careful backward kicks of an animal concealing its spoor. But now a memory surfaces in Landsman from the days following his father's death, of Uncle Hertz sitting crumpled like a wad of tissue in a corner of the kitchen on Adler Street, Shirttails hanging, no order to his hair, shirt misbuttoned, the dwindling contents of a bottle of slivovitz on the kitchen table beside him marking like a barometer the plummeting atmosphere of his grief.

The love story of Landsman and his wife, and the latter half of the mystery surrounding the murder (which involves Landsman's sister in a way I won't go into) are ultimately the most successful aspects of the book. They touch meaningfully on deep passion, loneliness, the battle to be oneself, and the question of the holy vs the ordinary.

I was a big fan of Chabon's The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay. While the parts of this book do not always create as complete a satisfying whole, there is a lot to enjoy in Chabon's latest.

No comments:

Post a Comment