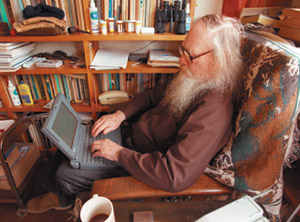

Inveterate wordsmith and drinker Hayden Carruth was born in 1921 in Connecticut U.S.A. He lived most of his adult life in Vermont, teaching and writing something like thirty books of poetry and criticism. His poems can observe the hardships of rural life, ruminate on his skepticism, or express his politics. He is capable of an as effusive an elegy as anyone but I feel like he's celebrating that place or that life "as it was" - no romantic he. He is a self described "pessimist and grump." His poems are unsentimental, the forms are simple and have jazz influence, his diction plain, his tone curmudgeonly, you can hear the gravel of drink and the lilt of New England in his voice. Here is a frank portrait of him done for the University of Chicago Magazine. A little excerpt:

Writes Pulitzer-winning poet Galway Kinnell, “More than in the case of any other poet, Carruth responds to Whitman’s words: ‘I was the man, I suffer’d, I was there.’”For Carruth struggle has been the stuff of life and poetry. “If you’ve got any courage and any sense of responsibility, you’ll do what you have to do,” he observes. “I don’t give myself any extraordinary credit for that. But the difficulties were there and the difficulties made my poetry better. I’m convinced of that.”

I'll include some earlier poems and some from his more recent Doctor Jazz - which feels to me like a departure - including a section called The Afterlife, a section on Basho the Japanese poet - the first poem is from that set - I think it is wickedly funny, another set he calls Faxes, and an impressive elegy to his daughter, whom he has outlived. I adore the poem Scrambled Eggs and Whiskey.

Emphysema

Had you air, Basho?

I mean enough to climb those

mountains? Or did you

stop every ten steps,

leaning on your staff and gasping

like a fish ashore?

The Way of the Coventicle of the Trees

Just yesterday afternoon I heard a man

Say he lived in a house with no windows

The door of which was locked on the outside.

This was at a party in New York, New York.

A deep Oriental type, I said to myself,

One of them indescribable Tebootans who

Habitate on Quaker Heights and drink

Mulled kvass first thing every morning

With their vitamins. An asshole. And

Haven't I more years than he? Haven't

I spent them looking out the window

At the trees? Oh the various trees.

They have looked back at me with their

Homely American faces: the hemlocks

And white birches of one of my transient

Homes, the catalpas and honey locusts

Of another, the sweet gum and bay and

Coffee trees, the hop hornbeam and the

Spindle tree, the dogwood, the great.

Horse chestnut, the overdressed pawpaw

Who is the gamin of that dominion.

Then, behind them, the forest, the sodality.

What pizzazz in their theorizing! How fat

The sentimentibilities of their hosannas!

I have looked at them out the window

So intently and persistently that always

My who-I-am has gone out among them

Where the fluttering ideas beckon. Yes,

We've been best friends these sixty-nine

Years, standing around this hot stove

Of a world, hawking, phewing, guffawing,

My dear ones, who will remember me

For a long, long time when I'm gone.

Words in a Certain Appropriate Mode

It is not music, though one has tried music.

It is not nature, though one has tried

The rose, the bluebird, and the bear.

It is not death, though one has often died.

None of these things is there.

In the everywhere that is nowhere

Neither the inside nor the outside

Neither east nor west nor down nor up

Where the loving smile vanishes, vanishes

In the evanescence from a coffee cup

Where the song crumbles in monotone

Neither harmonious nor inharmonious

Where one is neither alone

Nor not alone, where cognition seeps

Jactatively away like the falling tide

If there were a tide, and what is left

Is nothing, or is the everything that keeps

Its undifferentiated unreality, all

Being neither given nor bereft

Where there is neither breath nor air

The place without locality, the locality

With neither extension nor intention

But there in the weightless fall

Between all opposites to the ground

That is not a ground, surrounding

All unities, without grief, without care

Without leaf or star or water or stone

Without light, without sound

anywhere, anywhere. . .

Emergency Haying

Coming home with the last load I ride standing

on the wagon tongue, behind the tractor

in hot exhaust, lank with sweat,

my arms strung

awkwardly along the hayrack, cruciform.

Almost 500 bales we've put up

this afternoon, Marshall and I.

And of course I think of another who hung

like this on another cross. My hands are torn

by baling twine, not nails, and my side is pierced

by my ulcer, not a lance. The acid in my throat

is only hayseed. Yet exhaustion and the way

my body hangs from twisted shoulders, suspended

on two points of pain in the rising

monoxide, recall that greater suffering.

Well, I change grip and the image

fades. It's been an unlucky summer. Heavy rains

brought on the grass tremendously, a monster crop,

but wet, always wet. Haying was long delayed.

Now is our last chance to bring in

the winter's feed, and Marshall needs help.

We mow, rake, bale, and draw the bales

to the barn, these late, half-green,

improperly cured bales; some weight 150 pounds

or more, yet must be lugged by the twine

across the field, tossed on the load, and then

at the barn unloaded on the conveyor

and distributed in the loft. I help-

I, the desk-servant, word-worker-

and hold up my end pretty well too; but God,

the close of day, how I fall down then. My hands

are sore, they flinch when I light my pipe.

I think of those who have done slave labor,

less able and less well prepared than I.

Rose Marie in the rye fields of Saxony,

her father in the camps of Moldavia

and the Crimea, all clerks and housekeepers

herded to the gaunt fields of torture. Hands

too bloodied cannot bear

even the touch of air, even

the touch of love. I have a friend

whose grandmother cut cane with a machete

and cut and cut, until one day

she snicked her hand off and took it

and threw it grandly at the sky. Now

in September our New England mountains

under a clear sky for which we're thankful at last

begin to glow, maples, beeches, birches

in their first color. I look

beyond our famous hayfields to our famous hills,

to the notch where the sunset is beginning,

then in the other direction, eastward,

where a full new-risen moon like a pale

medallion hangs in a lavender cloud

beyond the barn. My eyes

sting with sweat and loveliness. And who

is the Christ now, who

if not I? It must be so. My strength

is legion. And I stand up high

on the wagon tongue in my whole bones to say

woe to you, watch out

you sons of bitches who would drive men and women

to the fields where they can only die.

Because I Am

in mem. Sidney Bechet, 1897-1959

Because I am a memorious old man

I've been asked to write about you, Papa Sidney,

Improvising in standard meter on a well-known

Motif, as you did all those nights in Paris

And the World. I remember once in Chicago

On the Near North where you were playing with

A white band, how you became disgusted

And got up and sat in front next to the bandstand

And ordered four ponies of brandy; and then

You drank them one by one, and threw the empty

Glasses at the trumpet-player. Everyone laughed,

Of course, but you were dead serious - sitting there

With your fuzzy white head, in your rumpled navy

Serge. When you lifted that brass soprano to your

Lips and blew, you were superb, the best of all,

The first and best, an Iliad to my ears.

And always your proper creole name was mis-

Pronounced. Now you are lost in the bad shoadows

Of time past; you are a dark man in the darkness,

Who knew us all in music. Out of the future

I hear ten thousand saxophones mumbling

In your riffs and textures, Papa Sidney. And when

I stand up trembling in darkness to recite

I see sparkling glass ponies come sailing at me

Out of the reaches of the impermeable night.

I don't think I can resist giving you some of Dearest M - . It's a sixteen-page elegy Carruth wrote for his daughter. Here's just a little bit:

Martha did her painting in private. We rarely

saw her at work.

If by chance we did, she would stand pointedly

in front of her easel, shielding the canvas

from our view. Similarly, she did not talk

about her painting, perhpas because she was

self-taught and didn't know the words -

but that's nonsense.

She was as language-driven as her father,

she had plenty of words. Bujt process was

something she did not wish to discuss.

Her paintings

were neither representational nor abstract.

She painted what she saw, supplying color and contrast

from the deepest recesses of her imagination,

as when one dreams

of what one has seen just before falling asleep.

An outdoor table and umbrella

by the sea with a white sailboat in the distance

and the shadow of the umbrella falling just so,

steeply pitched across the astonishing pineapple

and the bottle of wine.

Can a father recover his daughter in a painting?

Or in an orange-and-umber blouse he gave her

ten years ago?

Well, sometimes the heart in its excess enacts

such pageantry. But it is hollow, hollow.

...

The apple tree is gone. Eurydice has gone back

to hell, weeping and grim, betrayed. The night

is Pluto's cave. I've turned on all the lights

in this little house on the hill, my defiance

of metaphysical reality and the Niagara-Mohawk

Power Corporation. Idly, as so often, I am

staring at my watch, the numbers clicking away,

hours, minutes, seconds, but time is the most

unrealizable quantity. How long has Eurydice

been gone - a moment or always? And now

suddenly the lights go off. Something somewhere

is broken. The autumn wind has blown down

a tree across the lines. Where did I put that candle

I used to have? Somewhere a glitch is glitching, yet

this is a familiar place, I can move in the dark.

Martha was dead for two minutes, then two hours,

then ten, and will it become a day, two days, with her

not here? Impossible. I cannot think it.

Yet the lighted numbers on my watch keep turning,

ticking and turning. The numbered pages of my books

smolder on my shelves, surrounding me. Alas my dear,

alas. Time and number are a metaphysical reality

after all.

Scrambled Eggs And Whiskey

Scrambled eggs and whiskey

in the false-dawn light. Chicago,

a sweet town, bleak, God knows,

but sweet. Sometimes. And

weren't we fine tonight?

When Hank set up that limping

treble roll behind me

my horn just growled and I

thought my heart would burst.

And Brad M. pressing with the

soft stick and Joe-Anne

singing low. Here we are now

in the White Tower, leaning

on one another, too tired

to go home. But don't say a word,

don't tell a soul, they wouldn't

understand, they couldn't, never

in a million years, how fine,

how magnificent we were

in that old club tonight.

2 comments:

I like your post here about Hayden Carruth.

Thank you, Andrew. It was nice to discover your site as well.

Post a Comment