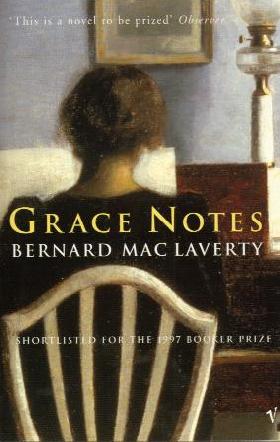

I remember being a guest on a public radio interview show in Chicago a number of years ago after having directed Virginia, a play about the life of Virginia Woolf written by Irish novelist Edna O'Brien from the writings of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Vita Sackville West, and the biography by Woolf's nephew Quentin Bell. It was a project I had considerable difficulty getting done but I had loved it enough to keep pitching it to theaters for five years until one producer (thanks, Patrick) finally had the interest in and the guts to do it. It became surprisingly successful and played for months and some cast members and I were invited on to this radio show where the host basically told me I wasn't qualified to direct it because I was a man and proceeded to side-line me and speak only to the charismatic actress who played the title role. In addition to wounding my ego and being a silly point to make given that the production was such a hit, I thought it really missed the boat about what artists do. They imagine. A good production by a female director would have been equally valid and no doubt would have brought insights that I hadn't had about the material and how it reflected Woolf's life and work, but it would not necessarily have been any better for her having had two X chromosomes and all the attendant bits that those usually confer upon the recipient. Can only old men direct King Lear? What about the insights the director should have about Cordelia - should that actress work with a woman and the king with a man? How old should he be? 50, as Lear might have been to be "old" in his day or 90 as he would be now? Perhaps we should only hire directors who have shared the same zip code as their characters, as they will have the proper geographical insight. You get my point. I think this talk show host might have had a bit problem with Bernard MacLaverty's Grace Notes, as his central character was not only a woman, but a pregnant one who gives birth, nurses, suffers depression that might be post-partum, and deals with her relationships with her mother and abusive boyfriend. I found it a real example of creative imagination.

I remember being a guest on a public radio interview show in Chicago a number of years ago after having directed Virginia, a play about the life of Virginia Woolf written by Irish novelist Edna O'Brien from the writings of Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Vita Sackville West, and the biography by Woolf's nephew Quentin Bell. It was a project I had considerable difficulty getting done but I had loved it enough to keep pitching it to theaters for five years until one producer (thanks, Patrick) finally had the interest in and the guts to do it. It became surprisingly successful and played for months and some cast members and I were invited on to this radio show where the host basically told me I wasn't qualified to direct it because I was a man and proceeded to side-line me and speak only to the charismatic actress who played the title role. In addition to wounding my ego and being a silly point to make given that the production was such a hit, I thought it really missed the boat about what artists do. They imagine. A good production by a female director would have been equally valid and no doubt would have brought insights that I hadn't had about the material and how it reflected Woolf's life and work, but it would not necessarily have been any better for her having had two X chromosomes and all the attendant bits that those usually confer upon the recipient. Can only old men direct King Lear? What about the insights the director should have about Cordelia - should that actress work with a woman and the king with a man? How old should he be? 50, as Lear might have been to be "old" in his day or 90 as he would be now? Perhaps we should only hire directors who have shared the same zip code as their characters, as they will have the proper geographical insight. You get my point. I think this talk show host might have had a bit problem with Bernard MacLaverty's Grace Notes, as his central character was not only a woman, but a pregnant one who gives birth, nurses, suffers depression that might be post-partum, and deals with her relationships with her mother and abusive boyfriend. I found it a real example of creative imagination.MacLaverty brings a great deal of imagination not merely to imagining the fact of his character's sex, but to having her body, experiencing the pain of her depression, the certainty it will never leave, and the feeling of lightness and surprise when it does. He also tackles the job of finding words to describe music, Catherine is a composer, what it is like to hear sounds inside your head - not hallucinations - music one knows is not real but which one hears nonetheless. What one might do with those sounds if they are the raw materials for one's creative art, and what it is like to face the finality of one's composition and deal with the amorphous and interior having become indelible and public. When he uses musical terminology to describe the music, e.g. describing a phrase as "fugue-like" I found it far less effective that when he went for simile and metaphor:

Darkening and growing, rising and falling by the narrowest of interval. Plaiting bread. Her mother's hands, three pallid strands, pale fingers over and under, in and out. Weaving. Like ornament in the Book of Kells. Under and over, out and in. Like pale fingers interlocked in prayer. Grace notes with a vaguely Celtic flavour. More and more threads slowly and imperceptibly surround what the violins are saying, repeating over and over again to themselves.

I also enjoyed his description of an creator dealing with making their art in the undeniable presence of their feelings

But she didn't dare mention the worst thing of all. To write something really dark, despairing even, is so much better than being silent. If you're depressed your mind says there's no point in writing anything. You just want to sit with your mouth hanging open - your mind full of scorpions. There was no formula for getting around that.

MacLaverty also writes passages in the book during which Catherine deals not with the idea of depression, but with the small realities that are the experience of it:

She turned in the bed - tried to bunch up her pillows to be more comfortable. Tried to stop worrying. The repetition of thoughts which caused her pain amazed her. Why did she continually do it? Like picking at a scab on her. Or her tongue probing as the socket of a recently pulled tooth. It prevent ed healing and she knew it prevented healing. Yet she did it. The best way to stop doing it was to invite other things into her head. But then there was always the underlying knowledge that she was thinking of this thing to stop thinking about what she didn't want to think about.

I found this book full of patiently described insights about being inside of difficult human feelings, and that is the kind of novel I really value. There are two choices this book makes that are difficult. One is the reliance it places on the reader having some familiarity with classical music. It makes numerous references not only to good old Bach, Mozart and Beethoven, but also to the composers Britten, and Messiaen, to Poulenc and his Gloria, to Janacek's Galgolitic Mass and piano sonata. Laverty references sounds Catherine hears in a Ukranian church as being like the voices of Pinza or Christoff. These are specific references that are very familiar to me and added a lot of visceral substance to the descriptions. I'm not sure what reading this novel would be like if those were just words. The second choice he makes is a structural one. Laverty chooses to tell this story in two sections - the first is Catherine's return home following the death of her father her struggle to reconcile her identity as a modern woman with her past and the more "traditional" lives of her parents and childhood neighbors- an composer of edgy modern music among people who love a good old fashioned song you can hum and tap your foot to, a mother of a child had out-of-wedlock among devout Catholics, someone dealing with depression versus a generation who didn't speak of feelings and dealt with them through prayer and hard work. She comes home after a long estrangement and must walk through the conflict , the impatience, the guilt that this produces. And MacLaverty offers us no pat answers. But, as if to some way respond to what lies behind her experience of this visit home, he offers us the book's second section of events which occurred earlier in time, during which she met and left her lover, had her child, and composed an important piece of music. It reveals the person behind the behavior of the first part but it does not explain away the conflicts or provide resolution. He plays with time throughout the novel - quickly moving back and forth in any given moment. This is a more radical movement of the book's "present" and its effect is best described by a passage in the book during which a composer whom Catherine meets in school speaks to the students:

Huang Zaio Gang had talked about time - about how in music it could shrink and expand. Again making small chopping motions with his hand and little movements of his head, he had said that time could be sectioned and moved around. Music was not linear as some people would have us believe. In the two monumental movements of the Beethoven opus 111 time could stop altogether - like a yoga slowing his heartbeat. The arietta was music from a different planet - a different timescale - out among the stars, free from the laws of time and space. No matter how many times he heard the 'adagio molto semplice e cantabile' he was forced to accept that the world, and our place within it, was infinitely mysterious.

This post along with this one constitute my thoughts on Bernard MacLaverty's Grace Notes.

Next up - Thirteen by Sebastian Beaumont. Scott Pack raved about this one and I'm hooked.

No comments:

Post a Comment