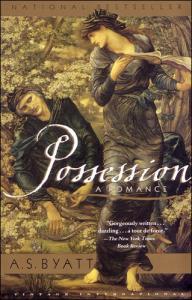

I'm Back on the Possession bandwagon, I'm glad to say, even if the cause was the fact that the guests in the hotel room next to our's had the television blaring at 3:00 am. I only have about 50 pages to go and I am taken by the multiple levels of satisfaction to be had - the intellectual mystery, the two romances - one in the past the other in the present - the literary ventriloquism (Byatt writes as the two Victorian writers Randolph Ash and Cristabel LaMotte in both poetry and epistolary prose, a young aspiring Breton author, Ash's wife Ellen, LaMotte's friend and housemate Blanche, and several of contemporary scholars who study each of these people.) One of the novels greatest pleasures is the variations on the theme that Byatt has composed on the inequities faced by women - in romance (past and present), in arts, and in scholarship. Late in the novel, poet Christabel LaMotte takes refuge with her cousin's family in Brittany. Her young cousin is an aspiring writer and in LaMotte finally finds both a role model and an honest reader. The excerpts from her journal to which the reader is privy seamlessly integrate the genesis of the young writer's art and the uncovering of the mystery that sits at the plot's center. The scene in Brittany is set during the Black Months, a time for traditional storytelling around the fire. Byatt puts fine versions of folk tales into the mouths of her characters that form an interesting meeting of the oral and the written traditions:

I'm Back on the Possession bandwagon, I'm glad to say, even if the cause was the fact that the guests in the hotel room next to our's had the television blaring at 3:00 am. I only have about 50 pages to go and I am taken by the multiple levels of satisfaction to be had - the intellectual mystery, the two romances - one in the past the other in the present - the literary ventriloquism (Byatt writes as the two Victorian writers Randolph Ash and Cristabel LaMotte in both poetry and epistolary prose, a young aspiring Breton author, Ash's wife Ellen, LaMotte's friend and housemate Blanche, and several of contemporary scholars who study each of these people.) One of the novels greatest pleasures is the variations on the theme that Byatt has composed on the inequities faced by women - in romance (past and present), in arts, and in scholarship. Late in the novel, poet Christabel LaMotte takes refuge with her cousin's family in Brittany. Her young cousin is an aspiring writer and in LaMotte finally finds both a role model and an honest reader. The excerpts from her journal to which the reader is privy seamlessly integrate the genesis of the young writer's art and the uncovering of the mystery that sits at the plot's center. The scene in Brittany is set during the Black Months, a time for traditional storytelling around the fire. Byatt puts fine versions of folk tales into the mouths of her characters that form an interesting meeting of the oral and the written traditions:I can't write down Gode's way of telling things. My father has from time to time encouraged her to tell him tales which he has tried to take down verbatim, keeping the rhythms of her speech, adding nothing and taking nothing away. But the life goes out of her words on the page, no matter how faithful he is. He said once to me, after such an experiment, that he saw now why the ancient Druids believed that the spoken words was the breath of life and that writing was a form of death.I thought those interesting, perhaps even risky, words to put into a book about writers and writing. As though Byatt were purposely calling our attention to the potential of the writer's words to fail to convince, even as she hopes to convince us of the verrisimilitude of her multiple universes. Or perhaps she is reminding us that what we are reading is, too, a tale and that written words cannot possibly do justice to the actual events.

Byatt takes on her theme of women and where they possess and are denied power as well as another theme - the scientific and rational world versus the world of art, impression, and affect (these are both interestingly embodied in Ash who is both a scientist and a poet) - in verse as well as prose. Here's an excerpt I particularly liked:

Know you not that we Women have no Power

In the cold world of objects Reason rules,

Where all is measured and mechanical?

There we are chattels, baubles, property,

Flowers pent in vases with our roots sliced off,

To shine a day and perish. But you see,

Here in this secret room, all curtained round

With Vaguest softness, all dimly lit

With flickerings and twinklings, where all shapes

Are indistinct, all sounds ambiguous,

Here we have Power, here the Irrational,

The Intuition of the Unseen Powers

Speaks to our women's nerves, galvanic threads

Which gather up, interpret and transmit

The unseen Powers and their hidden Will.

This is our negative world, where the Unseen,

Unheard, Impalpable, and Unconfined

Speak to and through us - it is we who hear,

Our natures that receive their thrilling force.

Come into this reversed world, Geraldine,

Where power flows upwards, as in the glass ball,

Where left is right, and clocks go widdershins,

And women sit enthroned and wear the robes,

The wreaths of scented roses and the crowns,

The jewels in our hair, the sardonyx,

The moonstones and the rubies and the pearls,

The royal stones, where we are priestesses

And powerful Queens, and all swims with our Will.

4 comments:

I did an Honours paper in 1995 called Biographical Fictions and this book was on the course. It was a trendy paper at that time. We did Flaubert's Parrot, and Tristram Shandy amongst others. The Stone Diaries won the Pulitzer that year, and Lloyd Jones got in trouble for Biografi (which was made up but put in the non-fiction section by some bookshops in England). I remember finding this book incredibly compulsive, and loving the inter-textuality of it (if that's a word). With later books I got a bit bored of this trick, and the trick of pretending history was the same as fiction. Sometimes I find Byatt a bit coldly intellectual, but in this book she really kept her complexity and wrote a real page-turner (I think).

Goosebumps. I love this book so much.

Sheila - I can really see why you love Ellen - amazing character.

To me, she's the linchpin of the whole thing. Because her story is never really known - it's THERE, it EXISTS - it's just that she never wrote any of it down ... the journal was her smokescreen for that terror and panic at the wrong-ness of her ... she drowned herself in domesticity and yet never could really enjoy it because there wasn't that physical aspect of it (sex with husband, basically - and children) to make it all meaningful. That line: "she was his slave". My God.

I will never forget her.

Post a Comment