This weekend we watched John Schlesinger's 1971 Sunday Bloody Sunday and Mike Nichols made for television version of Tony Kushner's Angel's in America, two films about living in a time of changing social mores, each as distinct in its subject matter and techniques as are the times they describe.

Although I lived through most of the 60s and all of the 70s, this was the first time I had seen Sunday Bloody Sunday. I have seen Glenda Jackson act many times (including on stage in a brilliant production of Eugene O'Neill's Strange Interlude) and she seems the perfect choice for Schlesinger's subtle, verité peep through the keyhole as staid, middle-class England, barely recovered from the hardship of their post-World War II deprivation, began twisting and shouting with John, Paul, George and Ringo, away from their nice cup of tea by the electric fire and toward a world that embraced marijuana, rock 'n roll, and free love. In this film, set to a soundtrack of Mozart's Cosi fan Tutte, another piece about saying goodbye to an old way of loving, a Jewish doctor, played by Peter Finch, and a middle class employment counselor (Glenda Jackson) both fall in love with an artist, and he with them (separately). We watch her walk the line between an old way of living, with a traditional marriage, Sunday dinner with Yorkshire pudding and strawberries with cream, and life in which you can possess no one. Yet Jackson's character cannot completely tow that line, she wants him all for herself. Peter Finch's character is gay in a society that criminalized homosexuality. He moves between worlds where he is closeted - his medical practice, his family - and those in which he lives openly: with some of his friends. He tries, in this changing society, to find happiness in love, if not complete openness. The film's visual language and its script are as down-to-earth realistic as you can get - no acting here - very much counter to the theatrical tradition that you can see on British stages and in British film, you seem to witness real life. Contrastingly, at the end, Finch has a direct address soliloquy to the film audience, breaking the mold of cinematic form just as the society Schlesinger is describing is trying to break free of its form.

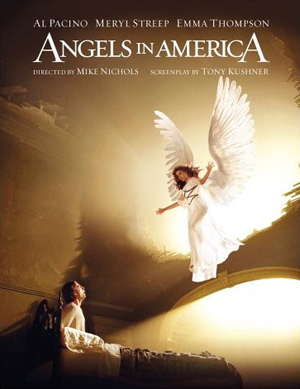

Tony Kushner's epic play in two parts, Angels in America, rocked my world when I saw the original production on Broadway. Mike Nichols' film made for HBO a couple of years ago has quite a cast - Meryl Streep, Al Pacino, Emma Thompson, Jeffrey Wright, and Ben Schenkman are all magnificent. In some ways this piece is really made for the live theater. It's poetic language is like an operatic aria, it's fantasy works better with rolling platforms and when you can see the wires on which the angel flies in. It's virtuosic flights of fancy - bringing together Roy Cohn (the lawyer) with the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg (whom he helped condemn to death for treason), she sings him a lullaby in Yiddish as he dies of AIDS - have a, well... theatricality about them. They're loud, un-real, or really anti-real, deliciously so, and the million dollar crane shots of the Bethesda fountain in Central Park and the trip to the Antarctica in Harper's mind (Harper is the valium-popping wife of a mormon, Republican lawyer who figures out he is gay - you see what I mean?) well those shots seem wrong. Unlike Sunday Bloody Sunday, this film does not try to be verite, the shots are more rhapsodic. But its cinematic story telling is fairly conventional and somehow in trying to show what these fantasies "really look like," they end up looking silly. This might have been a very different film if someone like Michel Gondry (The Science of Sleep) had directed it. But most of the acting is so wonderful I found myself moved and captivated by this visionary work all over again, especially in Part II where the film seemed to find its footing. Or maybe I just got used to it.

Angels in America, like Sunday Bloody Sunday, is looking at a world where the old stories about life and love aren't holding up any more. Roy Cohn cannot live the lie of being straight with Kaposi's sarcoma lesions all over him. Joe Pitt, the Republic mormon lawyer cannot come out to himself, but his wife knows he does not love her. Her loneliness turns into anxiety about the ozone layer and finally to psychosis. Joe comes out to his mother in a moment of desperation on a pay phone and she comes to New York a world completely alien to her life as a mormon in Utah. But the beautiful thing about this work is that no one is who you think they will be. Republicans are not all straight, mormon moms are not gay-hating religious fanatics unable to survive in the big city, drag queens are nurses AND can hold a serious political conversation, sick men with AIDS can be prophets, the fearful can be courageous, and the dying can come back to life. If you have an expectation about how life is supposed to turn out, prepare for it to be broken, and beautifully. Because is you have to be traumatized, it might as well be gorgeous.

This film too ends with the central characters breaking the "fourth wall" and speaking to their contemporary audience, here it is a little less startling because a theatrical language has been established, but it is still unusual for film. These thematically similar but stylistically diverse films both use this technique because they were trying to help their own day's audience see a social revolution they were a part of. It was moving to observe how, no matter what that particular time looked like, the way humans experience change doesn't change. A society may plan a revolution, or one may erupt, but in each person an evolution must occur in its own fashion, usually with some pain and some blood. Even though it was unintentional, I found it fascinating to watch these two films side by side - one slice-of-life, the other high fantasy. They both tell us that world has not yet arrived. It will continue to change. Continue to surprise us.

3 comments:

Thanks for the reviews. I haven't seen Sunday Bloody Sunday but now want to find a copy of it. I didn't see Angels in America on stage. At the time, it just seemed like such a depressing concept, I didn't think I wanted to experience it. When the HBO movie aired, all my husband could say was "Don't you wish you had gone with me to the theatre to see this?". And, of course, I did wish so. In the HBO film, the acting was brillant, and it was interesting to see how the obvious theatrical conventions were carried over to the screen, some more successfully than others. I think you have captured well the essence of the film. Now I just hope for a decent stage revival some day of Angels in America.

Oh, I meant to add: I liked the crane shots of the Bethesda fountain, although I did find them perplexing at first. I'll have to think about your comments about the real/unreal aspect of them and them not fitting in with the film. Sometimes, when I pass certain entrances to Central Park, I think about those shots and want to take a detour to walk down the Mall to the fountain. Not too often that I can though. :) Guess that means that I found them rather poignant -- or at least memorable -- that I recall the shots, and then the movie, and all of the themes in the movie.

Speaking of revolutions. Less than 20 years ago Estonia was in conflict with Russia. The Singing Revolution inspired thousands to come together and revolt through singing. (There is a great Documentary about Estonia's Singing Revolution: http://singingrevolution.com) It’s an emotional insight to the revolution.

Post a Comment