How can such a little volume be about so much? We Have Always Lived in The Castle by Shirley Jackson is about what people do when they love each other deeply, what people do when they hate each other, and what people do when they fear each other. It is about the role that imagination can play when you need to have enemies, and also when you need to have order and love in your life. It's about seeing things from the outside in versus seeing things from the inside out. It is such a remarkable and elemental story I scarcely want to breathe a word about it to you so that I don't ruin your experience of it. This is at once a cozy little story, simply written, a tale of desperate love, and a horror story. Here's a taste.

Helen Clarke said, "Do you suppose that people would really be afraid to visit here?" and Uncle Julian stopped in the doorway. He had put on his dandyish tie for company at tea, and washed his face until it was pink. "Afraid?" he said. "To visit here?" He bowed to Mrs. Wright from his chair and then to Helen Clarke. "Madam," he said and "Madam." I knew that he could not remember either of their names, or whether he had ever seen them before.

"You look well, Julian," Helen Clarke said.

"Afraid to visit here? I apologize for repeating your words, madam, but I am astonished. My niece, after all, was acquitted of murder. There could be no possible danger in visitng here now."

Mrs. Wright made a little convulsive gesture toward her cup of tea and then set her hands firmly in her lap.

"It could be said that there is danger everywhere," Uncle Julian said. "Danger of poison, certain. My nice can tell you of the most unlikely perils - garden plants more deadly than snakes and simple herbs that slash like knives through the lining of your belly, madam. My niece - "

"Such a lovely garden," Mrs. Wright said earnestly to Constance. "I'm sure I don't know how you do it."

Helen Clarke said firmly, "Now that's all been forgotten long ago, Julian. No one ever thinks about it any more."

"Regrettable, " Uncle Julian said. "A most fascinating case, one of the few genuine mysteries of our time. Of my time, particularly. My life work," he told Mrs. Wright.

"Julian," Helen Clarke said quickly; Mrs. Wright seemed mesmerized. "There is such a thing as good taste, Julian."

"Taste, madam? Have you ever tasted arsenic? I assure you that there is one moment of utter incredulity before the mind can accept - "

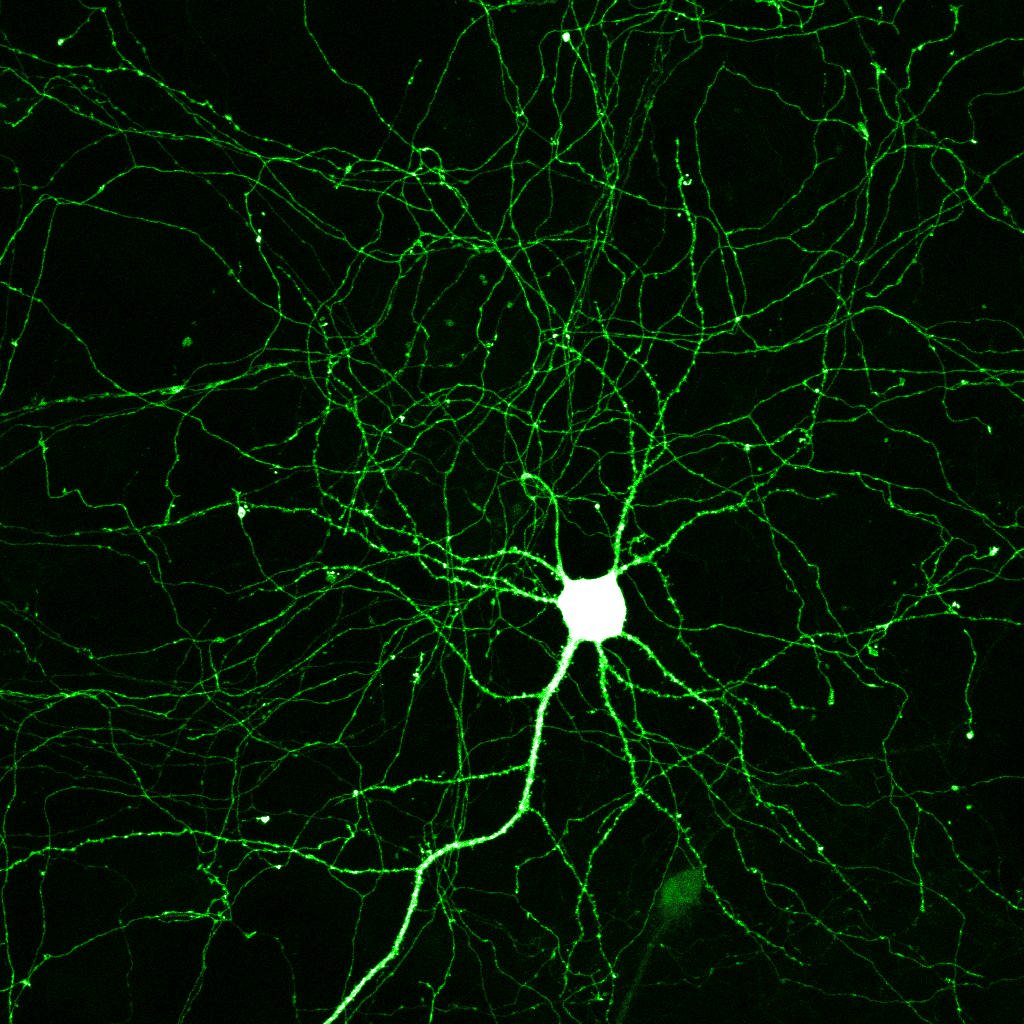

In both my lives as a theater artists and as someone who wants to learn about how the human brain produces our behavior, our psychology, I have felt it my duty to try imagine for a moment what it must be like to be inside the experience of someone else. Especially when I am considering the everyday experience of someone with a syndrome like autism - but really this applies to any phenomenon - it is most easy to come at another person (or a character in a work of theater) from the point of view that, faced with situation x, they probably experience it like me. Wrong. Wrong assumption. Dangerous assumption. It is the assumption that is at the route of most bad choices about relating to other people. It is the reason working to understand the person inside any form of suffering needs two things - hard science that makes rules and tests to check the innocent assumptions we all tend to make as human beings, and compassion that stops us from doing harm when we can't fix the problem.

This post along with this one constitute my review of We Have Always Lived in The Castle.