I'm not sure that Ron Chernow's Alexander Hamilton (Penguin Books, 2004) the bestselling biography and basis for Lin-Manuel Miranda's Broadway musical phenom needs any more hype, but here it goes. Chernow's book is a monument to one of America's most personally complex and influential founding figures. It is lengthy not because Chernow, as is often the case in modern biographers, can't manage to make choices about which bits of his research to share -- a toenails-and-all approach -- but because he integrates his subject's story with necessary personal and historical context. One cannot understand either the sheer amount of Hamilton's contribution to modern America: its constitution, party system, how voters are represented, how the state and federal governments relate, the system of checks and balances - nor the weight of these contributions, without understanding his role in the Revolutionary war, his relationship to George Washington (and by extension, who our first general and president was), and the opposition Hamilton faced from Thomas Jefferson (and who he was), James Madison (ditto), John Adams (ditto), and Aaron Burr (ditto), and having an overview of his most influential work The Federalist Papers.

Saturday, June 11, 2016

Saturday, May 14, 2016

Small bombs, large impacts, no simple explanations (Books - The Association of Small Bombs by Karan Mahajan)

In Karan Mahajan's The Association of Small Bombs (Viking, 2016), three boys set out on an errand one afternoon in Delhi. Only one of them returns. Tushar and Nakul, brothers, are hindu. They are killed by a terrorist's bomb. Their friend, Mansoor, is muslim. He survives, but with physical and emotional scars. Mahajan writes of the origins and the consequences of such "small" acts of devastation. They are perpetuated by just one or two individuals. The bombs are built with easily found materials and fit neatly in backpacks. The political perspective of the perpetrator and the pain of the survivors are similar in their intense myopia, but, as Mahajan writes:

The bombing, for which Mr. and Mrs. Khurana were not present, was a flat, percussive event that began under the bonnet of a parked white Maruti 800, though of course that detail, that detail about the car, could only be confirmed later. A good bombing begins everywhere at once.

A crowded market also begins everywhere at once, and Lajpat Nagar exemplified this type of tumult. A formless swamp of shacks, it bubbled here and there with faces and rolling cars and sloping beggars...

Sunday, May 1, 2016

People are more than objects in space (Books - A Doubter's Almanac by Ethan Canin)

Ethan Canin was already one of my favorite authors for having written For Kings and Planets, and I have frequently recommended his The Palace Thief and Emperor of the Air. With A Doubter's Almanac (Random House, 2016) Canin has written a "great" book, in the sense of giving expression to profound experiences, and also, I believe, in creating something whose meaning extends beyond its exemplars - the concerns of these specific characters, the obsessions of the period in which it was written - and has the potential to be enduring. Time will tell on that second point.

In some ways, Canin is writing about the same things he has always written - fathers and sons, success and failure, gut-smarts and brains - all within the scopes of the grandest of considerations: time and space. Time as it is experienced on a human scale, through one generation of a family experiencing another. Three generations of the Andret family are the focus of this novel. Space as it is described by a branch of mathematics called topology, which studies the interrelation of things, though not on the level they are visible in nature, on a hypothetical level of multiple dimensions. This is the focus of the work of Canin's protagonist, Milo Andret, who may be a genius in using math to describe such relationships but is profoundly disabled in forming a typical human bonds and severely limited even in insight into himself. In one scene, Canin describes Milo as having to touch his own face to understand that he was smiling.

In some ways, Canin is writing about the same things he has always written - fathers and sons, success and failure, gut-smarts and brains - all within the scopes of the grandest of considerations: time and space. Time as it is experienced on a human scale, through one generation of a family experiencing another. Three generations of the Andret family are the focus of this novel. Space as it is described by a branch of mathematics called topology, which studies the interrelation of things, though not on the level they are visible in nature, on a hypothetical level of multiple dimensions. This is the focus of the work of Canin's protagonist, Milo Andret, who may be a genius in using math to describe such relationships but is profoundly disabled in forming a typical human bonds and severely limited even in insight into himself. In one scene, Canin describes Milo as having to touch his own face to understand that he was smiling.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

The hyperfocus of life during illness, and the book as immersive technology (Books - Scarred Hearts by Max Blecher)

Scarred Hearts (Old Street Publishing) by Max Blecher was first published in Romanian in 1937, but did not reach English readers until 2008. The novel is set in a sanatorium in France, describing life there for tuberculosis patients. Although written in the third-person, Emanuel is clearly a stand-in for Blecher himself, who was diagnosed with Pott's Disease, a tuberculosis of the spine, at age 19. Treatment for this condition at that time immobilized patients in body-casts. They lay on their backs in special carriages which could be wheeled around in by people or horses, adding infantilization to their list of indignities. What is striking in this novel is that, in the face of death on a daily basis, most of Blecher's vividly drawn characters are still focused squarely on the banalities of daily living. Blecher writes in an adolescently effusive tone of Emanuel's lust, jealousy, urge to relieve the itching under his body cast, or his embarrassment at the smell of his body, given his limited ability to wash. That is not to say that he ignored pain, loss of function, or mortality, but the narrative style focuses less on the moment-to-moment shame of it than it does on the absurdity. When 19-year-old Emanuel learns of his diagnosis he writes:

In this book, context is all. Blecher immerses us first in the immediate urgency of a young man's crippling illness, once that is achieved, the impact of this brief novel succeeds because we know two things, only one of which was known to Blecher. One is the tragedy that the author would die at 29 years-of-age, something we are aware of as his character worries about his appearance before meeting a girl he is infatuated with. Don't waste time, I wanted to scream as I read, but he struggles any young lover would, despite being tied to a carriage and immobilized in a body cast. The second is the absurdity, that, given the year of Blecher's death (1938), he would never see the war which would focus the entire world myopically on an infection of its own and that, if he hadn't died of tuberculosis, as a Romanian jew, he would likely not have lived but a few more years.

So many horrific things had occurred, so sententiously and so calmly, during the last hour; so much catastrophe had taken place, that, exhausted as he was by the day's excitement, for a delirious, irrational moment Emanuel felt like laughing.As he rides the train with his father to Berck Sanatorium, Emanuel meets an old lady whose son is a long-time patient. She asks if he has an abscess?

'Yes, I do,' Emanuel replied with a certain brusqueness. 'What's it to you?'Blecher's narrative pulls us inside the hyperfocus of a life commanded by illness. Today we celebrate technologies like virtual reality that are supposedly unique for immersing viewers in a full sensory experience of, say, sitting in the cockpit of a plane or walking across a battlefield, but Blecher's writing reminds one that books can be equally effective at enveloping the reader in the sensations of an experience that are not actually occurring to them.

This time the old lady said nothing. In the calligraphy of wrinkles on her face there was a clear sign of some great sadness. In a half-voice she ventured to ask if the abscess had been fistulised...

'It's a good thing the abscess is not fistulised,' muttered the old lady.

'And if it were?' replied Emanuel absently.

'Ah well, then it's another matter...' and leaning into his ear she whispered breathlessly: 'The word at Berck is that an open abscess is an open gateway to death.'

In this book, context is all. Blecher immerses us first in the immediate urgency of a young man's crippling illness, once that is achieved, the impact of this brief novel succeeds because we know two things, only one of which was known to Blecher. One is the tragedy that the author would die at 29 years-of-age, something we are aware of as his character worries about his appearance before meeting a girl he is infatuated with. Don't waste time, I wanted to scream as I read, but he struggles any young lover would, despite being tied to a carriage and immobilized in a body cast. The second is the absurdity, that, given the year of Blecher's death (1938), he would never see the war which would focus the entire world myopically on an infection of its own and that, if he hadn't died of tuberculosis, as a Romanian jew, he would likely not have lived but a few more years.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

Innocence rescued in a modern literary fantasy (Books - The Children's Home by Charles Lambert)

I am a great admirer of Charles Lambert's books, having enjoyed his thriller-like works Any Human Face and The View from the Tower, his debut novel Little Monsters, and With a Zero at its Heart, a recent volume of brief poem-like episodes of memory, surprising to me for how they departed in style from his other published work. Never short on surprises, Lambert's latest is again a departure - I'd call The Children's Home (Scribner, 2016) equal parts dystopian fantasy, gothic tale, and parable. Reading across Lambert's work, I have observed a theme of betrayed innocence, which has been expressed in a story of disenfranchised children. Unlucky orphans have made their way into stories from Dickens to J. K. Rowling. I think that perhaps one appeal in tales like these is that, as a reader, I take on the perspective of that child. I can project my own not-knowing, my isolation, and sense of danger onto theirs - feel the risk, but safely, as this is art - and then later can defeat the adversity, feeling accomplished, knowledgeable, and secure.

In The Children's Home, though, Lambert has turned the form on its ear (not surprisingly). Here the protagonist, Morgan Fletcher, is a grown man - but perhaps not fully grown - and this is part of the point. He has been the victim of his mother's cruelty and has quite literally lost his face (read his sense of self). In the course of this story, it is a child, or band of children really, who help him grow up. The tale makes nods to literary predecessors - Orwell and Kafka - with a nameless Ministry that sates itself by devouring children - H.G. Wells and Ralph Ellison - with a protagonist whose interior and exterior faces are very much at odds. I think that I detect an homage to Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant, perhaps? As a thriller writer, Lambert knows how to create narrative tension by not answering all the reader's questions. As a poet, he holds back from explaining everything the reader wants to know, so that we insert our imaginations into the text. In Lambert's fantasy writing, the world is familiar and yet never quite what one expects (the sun rises in the West, for example) and the clues are subtle. It feels a very Lambertian reading experience that in paying close attention, this reader felt that he had teased out special details hidden just for him, felt rewarded, even accomplished, at the conclusion of The Children's Home.

In The Children's Home, though, Lambert has turned the form on its ear (not surprisingly). Here the protagonist, Morgan Fletcher, is a grown man - but perhaps not fully grown - and this is part of the point. He has been the victim of his mother's cruelty and has quite literally lost his face (read his sense of self). In the course of this story, it is a child, or band of children really, who help him grow up. The tale makes nods to literary predecessors - Orwell and Kafka - with a nameless Ministry that sates itself by devouring children - H.G. Wells and Ralph Ellison - with a protagonist whose interior and exterior faces are very much at odds. I think that I detect an homage to Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant, perhaps? As a thriller writer, Lambert knows how to create narrative tension by not answering all the reader's questions. As a poet, he holds back from explaining everything the reader wants to know, so that we insert our imaginations into the text. In Lambert's fantasy writing, the world is familiar and yet never quite what one expects (the sun rises in the West, for example) and the clues are subtle. It feels a very Lambertian reading experience that in paying close attention, this reader felt that he had teased out special details hidden just for him, felt rewarded, even accomplished, at the conclusion of The Children's Home.

Monday, April 4, 2016

Alexander Humboldt's broadreaching influence on modern science (Books - The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf)

Andrea Wulf's biography The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt's New World (Alfred A. Knopf, 2015) shares the irrepresable energy of her subject. Wulf convincingly contends that the German-born explorer, adventurer, scientist, and author (1769 - 1859) was the creator of our modern understanding of the natural world. His interests extended from volcanoes to plant-life, to climate, to the cosmos and his influence can be seen in the way we comprehend nature as something not to be ruled, but as something that human beings exist within - something complex and "alive." Humboldt is an ideal subject for reconsideration in a modern scientific biography. Wulf paints a picture of Humboldt as a contemporary outsider, offering strong support that he was gay. He warned in the 19th century of the impact humans could exert on climate. Finally, his expertise of the natural world was preserved in dozens of

volumes that were appreciated as much as repositories of

factual information as they were for their poetry. This passion helped father the contemporary environmental movement, influencing naturalists Darwin, Thoreau, and Muir. It can arguably be appreciated in our own era's melding of the arts and sciences in an effort to broaden understanding of our small place but potentially devastating impact in a very large and complex system.

Sunday, April 3, 2016

Bloomsbury myth-busting of the highest order (Books - Virginia Woolf: A Portrait by Viviane Forrester)

Viviane Forrester's Virginia Woolf: A Portrait (Columbia University Press, 2013), in 2013 is less strictly a biography than it is a literary myth-buster. If you are a fan of all things Bloomsbury, and I am an enthusiastic one, you are likely to be fascinated by new primary source material about Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Vanessa Bell, and the Duckworths. She uses this, a close reading of long-published letters, diaries and fiction, and a fresh frame-of-reference to reinterpret the famous relationships of Virginia Woolf to her father, husband, sister, and her own psyche. Her writing style is familiar and conversational, like a good literature professor leading a high-level seminar to share an original understanding of work she has reconsidered deeply. I don't know what it would be like to read this work without having a thorough grounding in Woolf's work, Leonard Woolf's diaries, and the famous Quentin Bell biography of Virginia Woolf, but I imagine it would be pointless. However, if you are an aficionado, the literary archeology is excellent, the writing accessible and clean, and the conclusions startling.

Sunday, March 6, 2016

The science of autism is a story of real people (Books - In a Different Key by John Donvan & Caren Zucker)

Ruth had stopped doubting herself the morning she saw Joe do a jigsaw puzzle upside down. For some time, she had been nagged by a feeling that he was not like her other children in some crucial way. Six months earlier, Joe had stopped speaking, even though, up to that point, he had seemed to be developing normally...

And then there were these puzzles. He was working on one just then, a map of the United States whose parts were sprawled, like him, all over the kitchen floor and through the doorway into the living room. He was getting it done: New Hampshire met Maine, and New Mexico snapped in next to Arizona. But he was getting it done fast, almost too fast, Ruth felt, for a two-year-old. On a hunch, she knelt down to Joe's level and pulled the map apart, scattering the pieces. She also, deliberately, turned each piece upside down, so that only the gray-brown backing was showing. Then she watched what Joe did with them

He seemed not even to notice. Pausing only for a moment, Joe peered into the pile of pieces, then reached for two of them. They were a match. He immediately snapped them together, backside-up, between his knees on the floor. It was his new starting point. From there he kept going, building, in lifeless monochrome, out of fifty pieces, a picture of nothing.

What John Donvan's and Caren Zucker's In a Different Key: The Story of Autism (Crown Publishers, 2016) is especially good at, is conveying a picture of autism historically, scientifically, and socially, by telling the stories of the people involved. One in 68 children have a diagnosis, so it's hard to live in today's America without hearing about autism. Understood as a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder, it is diagnosed based on impairments in communication, especially social relatedness, and a restricted repertoire of activity and interests. The dysfunctions it results in manifest themselves in different persons as impaired eye contact, failure to develop peer relationships, an absence of or delay in developing communicative speech, an inability to conceive of other people's mental states or emotions, lack of spontaneous imaginative play, inflexible adherence to routines which are disruptive to daily functioning, and persistent preoccupation with part of objects rather than their conventional uses, symptoms which must be present prior to three years-of-age to be diagnostically relevant and which often are noticed suddenly, after a period of apparently typical development.

Sunday, January 31, 2016

The Unexpected World of Cage Fighting and What It has to Do With Us (Books - Beast by Doug Merlino)

I am as guilty of it as the next person - reading for comfort. Either we read about worlds with which we are familiar or, and I think worse, to confirm what we believe we already know. I say 'what we believe we know' because that's the risk - isn't it? That we might learn something new, or that we might change our minds, and sometimes that comes in unexpected packages. I read Doug Merlin's Beast: Blood, Struggle, and Dreams at the Heart of Mixed Martial Arts (Bloomsbury USA, 2015) because Doug is a friend and, frankly, would never have read it if left to my own reading habits. I'm glad that I did.

Jeff Monson was, as usual, running late. He was trying to get his two-year-old daughter, Willow, to eat.

"Here comes the plane, Willow," he said in a singsong voice, holding out a spoon to the girl, who was sitting in her high chair. "Are you ready for the plane?"

Willow threw back her head, covered in red curly hair, laughed, and refused.

Monson wore shorts, flip-flops, and a T-shirt that stretched to cover his muscled frame. His head, which rose out of a triangular based of trapezius muscle, was bald. FIGHT was tattooed on the left side of his neck, directly above an exhortation to DESTROY AUTHORITY.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Coming of age in the footlights (Books - The Little Shadows - by Marina Endicott)

Award-winning Canadian novelist Marina Endicott is not widely known in the U.S., but she deserves to be. Her The Little Shadows (Doubleday Canada, 2011) is an entertaining, coming-of-age saga of three sisters, Aurora, Clover, and Bella, working for their supper on the vaudeville circuit circa 1912 with their widowed mother. Aside from simply being a good story, there were three things I particularly enjoyed about The Little Shadows.

This is a coming-of-age story about women rather than men, which is still a literary rarity. When it begins, the emphasis is on the sisters' act, how they function as one, as their survival depends upon its success. But as they mature, they become individuals as artists and women. The joy of the plot is tracing the development of their characters and how their talents shape them to be the women they become.

This is a coming-of-age story about women rather than men, which is still a literary rarity. When it begins, the emphasis is on the sisters' act, how they function as one, as their survival depends upon its success. But as they mature, they become individuals as artists and women. The joy of the plot is tracing the development of their characters and how their talents shape them to be the women they become.

Saturday, December 12, 2015

A tale of coming together while coming apart (Books - Sleeping on Jupiter by Anuradha Roy)

In Sleeping on Jupiter (2015, Hachette India) Anuradha Roy creates a tale of convergences. An Indian girl, Nomi, is orphaned when her parents are slaughtered in war. She is given refuge in an ashram, where she is sexually abused by the guru, after which she is adopted by a European woman and raised in Scandanavia. As a young woman she returns to India, to Jarmuli, the seaside town where the Ashram was located. Three older women, good friends, go on a long-planned trip to the same seaside town - a well-earned but final fun weekend, as one of them is becoming infirm. They make a pilgrimage to Jarmuli's famous temple. At the same time, one of the older women's sons has also made his way to Jarmuli for work, following the break-up of his marriage. And a young man tries to earn enough money to escape from under the abusive thumb of his uncle by working as a temple guide. These characters come to Jarmuli, some from darkness in their past, some with present woes. Their meeting is meant to have a redemptive ring to it, but Roy's beautiful lyrical prose doesn't seem to raise the convergence above coincidence.

Saturday, November 28, 2015

Life is more than what we know (Books - In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman)

A well-to-do Londoner, his marriage and his job as an investment banker in ruins as the economy collapses in 2008, receives a visit. Zafar, whom he knew in college, is of Bangladeshi birth, an orphan, a mathematical prodigy, an Oxford graduate, and a human rights lawyer. Agitated, traveling only with a backpack, Zafar arrives at our narrator's home and tells the remarkable story of how he came to be as he is now - a tale of contemporary Asian politics, English colonialism, and the Incompleteness Theorem of mathematician Kurt Godel.

In In the Light of What we Know by Zia Haider Rahman (Picador, 2014) story- telling itself is an important part of the story. Both who we are and how we're known, it explains, are narrative constructions.

In In the Light of What we Know by Zia Haider Rahman (Picador, 2014) story- telling itself is an important part of the story. Both who we are and how we're known, it explains, are narrative constructions.

Saturday, November 14, 2015

The Man Who Wouldn't Be Known (Books - A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara)

Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life (Doubleday, 2015) has been written about widely and short-listed for the 2015 Man Booker Prize. As I started it on the recommendation of my local bookseller this past summer, I had heard very little of the hooplah. I believed I was reading a typical modern tale of four friends who went to college together, chronicling their coming of age, their successes, failures and jealousies in relationships and work. But A Little Life defies this genre. The friends are an architect, an actor, an artist, and their friend Jude, around whom they and this story revolve. Jude is a man of great beauty, although he is never physically described by the author. He is brilliant and creative, although he makes his very ample living as an attorney. Yet with all of the accoutrements of success, Jude cannot allow himself be loved, so severely is he traumatized by abuse he suffered as a child.

Sunday, November 1, 2015

Revolution in thought and practice (Books - The Lunar Men by Jenny Uglow)

Erasmus Darwin, 18th Century physician, writer, grandfather of the more famous Charles, and one of the eponymous lunar men of Jenny Uglow's book, wrote in the later years of his life:

Credulitas. Credulity. Life is short, opportunities of knowing rare; our senses are fallacious, our reasonings uncertain; man therefore struggles with perpetual error from cradle to the coffin. He is necessitated to correct experiment by analogy, and analogy by experiment...If you live life with an ounce of curiosity in you, you likely recognize the longing Darwin so pithily expressed . If you, like Darwin, James Watt and Matthew Boulton inventors of the steam engine, Josiah Wedgwood potter and chemist, Joseph Priestley religious radical and the discoverer of oxygen, or any of the other principal characters in Uglow's The Lunar Men (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002), live to pursue your curiosities, then this is your creed.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

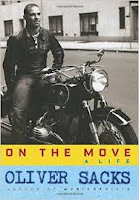

Two memoirists of passion (Books - Love is Where it Falls by Simon Callow & On the Move by Oliver Sacks)

In the last several months I read the memoirs of two fascinating, beloved, gay, British-born public figures. One was published recently, the other 15 years ago. One works in one of my areas of expertise - the arts - and the other in the other - the science of the brain. The authors were actor Simon Callow and Dr. Oliver Sacks. Their books are Love is Where it Falls (Penguin Books, 2000) and On the Move: A Life (Knopf, 2015). Their books are forthright and generous, the authors deeply giving of themselves, and they are crack writers. Knowing them now, as I do, it is fitting that these copies are signed.

Oliver Sacks has written so humanely and observantly of his patients' lives (for instance here and here), and so openly of his peculiar fascinations, that this memoir, and this is the third of his books that might be classified as such, was a welcome departure. Here, finally, Sacks scrutinized as deeply and wrote as openly about his own life - particularly his inner life. This was welcome not only in knowing more about so great a man and storyteller, but also because one read it in the context of his impending death (about which he wrote so beautifully here and here) and because one could feel in the narrative drive this desire to share it all before it was too late.

Early in Sacks's writing career, the great poet W. H. Auden said to Sacks

She had, she said, been walking down Piccadilly, musing on the fact that it was Moliere's birthday and that not a single actor in England would know, much less care. Musing on this sad reality, it had suddenly struck her that, yes, there was an actor in England who would know and care: me. And so she had gone into Fortnum's and ordered the wine and had it sent to me, to celebrate, with my actor friends, the great playwright's birthday.So begins an unlikely romance between a fierce, 70-year old theatrical literary agent, Peggy Ramsay, and 30-year-old actor Simon Callow. I find myself wanting less to write about the merits of this book than to quote from it. These two live passionately and are attracted to each other so relentlessly, because their taste in art is not so much an aesthetic about life's decor as a deeply held principle about the way to live it.

We must feel, that is everything. We must feel as a brute beast, filled with nerves, feels, and knows that it has felt, and knows that each feeling shakes it like an earthquake.or

I do so passionately believe that the only meaning of life is life, that to live is the deepest obligation we have, and that to help other people live is the greatest achievement. It's in that light that I see acting, and that alone.

Oliver Sacks has written so humanely and observantly of his patients' lives (for instance here and here), and so openly of his peculiar fascinations, that this memoir, and this is the third of his books that might be classified as such, was a welcome departure. Here, finally, Sacks scrutinized as deeply and wrote as openly about his own life - particularly his inner life. This was welcome not only in knowing more about so great a man and storyteller, but also because one read it in the context of his impending death (about which he wrote so beautifully here and here) and because one could feel in the narrative drive this desire to share it all before it was too late.

Early in Sacks's writing career, the great poet W. H. Auden said to Sacks

You're going to have to go beyond the clinical... Be metaphorical, be mystical, be whatever you need.This is really where Sacks's writing succeeds so magnificently in combining what is true with what feels true in a story. I cherish his writing and hope to celebrate his life in a live program in the coming year.

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Impressions of Napoli and Ferrara (Books - Neopolitan Novels by Elena Ferrante & How to Be Both by Ali Smith)

Elena Ferrante's Neopolitan quartet, composed of My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, and, The Story of the Lost Child, is a stunning portrait of the friendship between two women and particularly how the life of a great friend can become subsumed in one's own. It is a literary page-turner and arriving at the end of some 1,700 pages I experienced how masterfully structured it was. Ferrante's narrator is herself a writer and the quartet, especially the final volume, reflects on the process and consequences of writing. She manages to be smartly self-aware without becoming overly explanatory. Her mastery of craft is made plain to me when I think of the broad cast of some 40 characters with whom I had become familiar. The scene writing, as in the wedding reception that closes the first volume, brings the huge cast into spectacularly vivid focus, even while creating a tone that feels so of its period (late 50s/early 60s) that my mind's eye sees it in the Technicolor palate. I cannot recommend these enough.

I feared that Ali Smith's How to be Both might become twee because of its concept, but I should have known better. Smith has constructed a pair of interrelated tales, one set in renaissance Italy based on the life of fresco painter Francesco del Cossa and the other set in modern day Britain concerning a daughter mourning the death of her mother, an activist. The plots are cleverly referential of one another but don't yield their secrets easily. The concept, such as it is: these stories can be read with either as the first. In the order I read them (15th century first) the narrative keeps the reader working to understand what Smith's narrator sees. Without giving away too much, she/he sees aspects of the other narrative. In fact, each story's art making protagonist has a window into the other, and the effect for the reader is something like an infinity mirror. Smith's literary time travel is a puzzle of sorts, offering some intellectual smiles and even thrills at hearing the 'click' as a detail falls into place. I am a rabid fan of Smith's Artful and her themes of identity, loss, and the uses of art are visited here again but in a different guise. Smith loves to play with form, and to let you know it. If Artful was an argument (a narrative about the composition of a lecture on art), How to be Both is a more traditional immersive narrative experience, but one that plays with the tension between then and now, between life and death, between art and audience, and between visual and narrative form. You know those 'which writer would you invite to lunch questions?' Ali Smith would be one of my guests.

I feared that Ali Smith's How to be Both might become twee because of its concept, but I should have known better. Smith has constructed a pair of interrelated tales, one set in renaissance Italy based on the life of fresco painter Francesco del Cossa and the other set in modern day Britain concerning a daughter mourning the death of her mother, an activist. The plots are cleverly referential of one another but don't yield their secrets easily. The concept, such as it is: these stories can be read with either as the first. In the order I read them (15th century first) the narrative keeps the reader working to understand what Smith's narrator sees. Without giving away too much, she/he sees aspects of the other narrative. In fact, each story's art making protagonist has a window into the other, and the effect for the reader is something like an infinity mirror. Smith's literary time travel is a puzzle of sorts, offering some intellectual smiles and even thrills at hearing the 'click' as a detail falls into place. I am a rabid fan of Smith's Artful and her themes of identity, loss, and the uses of art are visited here again but in a different guise. Smith loves to play with form, and to let you know it. If Artful was an argument (a narrative about the composition of a lecture on art), How to be Both is a more traditional immersive narrative experience, but one that plays with the tension between then and now, between life and death, between art and audience, and between visual and narrative form. You know those 'which writer would you invite to lunch questions?' Ali Smith would be one of my guests. Still to come, capsules of Simon Callows' Love is Where it Falls, Olver Sacks's On the Move, and Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life and while-I-read impressions of Hiding in Plain Sight and Lunar Men.

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

David Grossman on his Writing Process

If you have loved David Grossman's fiction, as I have (see here on To the End of the Land), then you will appreciate this 2007 Paris Review interview with him on Arabs and Israelis, his writing process, and his life.

In recent years, I feel I’m less and less influenced by writers. I do not see this as a good sign, by the way. I want to be influenced by writers. I think it is a sign of being open...

...the books that really matter, the books that I cannot imagine my life without having written, are the more demanding ones, like The Book of Intimate Grammar, Be My Knife, See Under: Love, and the book I’m writing now. I may occasionally like to write an entertaining book, but I take literature seriously. You’re dealing with explosives. You can change a reader’s life, and you can change—you should change, I think—your own life.

Usually a lighter book will serve as a kind of recovery for me. I devastate myself when I write a certain kind of book—there is a process of dismantling my personality. All my defense mechanisms, everything settled and functioning, all the things concealed in life break into pieces, because I need to go to the place within me that is cracked, that is fragile, that is not taken for granted. I come out of these books devastated. I don’t complain, of course. This is how books should be written. But my way to recover from this sense of total solitude is to write books that will bring me into close contact with other people. I wrote The Zigzag Kid because I had to recover from The Book of Intimate Grammar and Sleeping on a Wire.

Saturday, May 23, 2015

Past inhabits present in the lives of 3 families (Books - The Turner House by Angela Flournoy; A Legacy by Sybille Bedford; & Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz)

Three family sagas are the subject of this post. What I like about this form is the intertwining of the characters' narratives with a sense of place and time. When it works well, I experience both the familiarity of people wanting, thinking and behaving, and the distance of an unfamiliar time and which gradually lessens, becoming more and more like my own. Sybille Bedford's A Legacy (Counterpoint, 1956, 1999) set in late 19th and early 20th century Germany, Naguib Mahfouz's Palace Walk (Doubleday, 1956, 1990) set in early 20th century Cairo, and Angela Flournoy's accomplished debut The Turner House, (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015) set in past and present day Detroit.

Saturday, May 16, 2015

Two formative men of the American Theatre (Books - A Life by Elia Kazan & Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh by John Lahr)

The life stories of two American Theatre makers monopolized my reading back in January: Elia Kazan: A Life, film and theatre director Kazan's hefty, probing memoir (Alfred A. Knopf, 1988) and Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (W.W. Norton & Co. 2014), John Lahr's deftly paced, thoroughly researched, deeply perceptive biography of the great playwright. Two men could not have had a greater influence on the structure and build of action, the feeling of innocence and epiphany, the rhapsodic music of text, the themes of individuality and of sex that were the coming-of-age of the American theatre and film in the 1930s - 1970s, than Williams and Kazan. Two men could not have been more superficially different - Kazan was the son of Greek immigrants, born in Turkey, a scrappy fighter, and relentless womanizer, Williams a grandson of an American preacher, delicate, gay, a virgin until twenty-six years of age - but fundamentally they were remarkably similar. Aside from their obvious love of theatre, both seemed dissatisfied with the restrictions of their world, were driven to create theatre to give veiled expression to a deep sense of personal failure, both felt outsiders and compulsively pursued relief in work or, failing that, one from drink and the other from sex. John Lahr's quotes a letter from Williams to Kazan:

The life stories of two American Theatre makers monopolized my reading back in January: Elia Kazan: A Life, film and theatre director Kazan's hefty, probing memoir (Alfred A. Knopf, 1988) and Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (W.W. Norton & Co. 2014), John Lahr's deftly paced, thoroughly researched, deeply perceptive biography of the great playwright. Two men could not have had a greater influence on the structure and build of action, the feeling of innocence and epiphany, the rhapsodic music of text, the themes of individuality and of sex that were the coming-of-age of the American theatre and film in the 1930s - 1970s, than Williams and Kazan. Two men could not have been more superficially different - Kazan was the son of Greek immigrants, born in Turkey, a scrappy fighter, and relentless womanizer, Williams a grandson of an American preacher, delicate, gay, a virgin until twenty-six years of age - but fundamentally they were remarkably similar. Aside from their obvious love of theatre, both seemed dissatisfied with the restrictions of their world, were driven to create theatre to give veiled expression to a deep sense of personal failure, both felt outsiders and compulsively pursued relief in work or, failing that, one from drink and the other from sex. John Lahr's quotes a letter from Williams to Kazan:Friday, March 20, 2015

3-D tour through brain space for Brain Awareness Week

I talked to curious students about the Brain at BiobBase yesterday and took a really amazing tour through a 3-D brain in a planetarium...no, really. Check out my Brain Awareness Week blog by clicking here and scrolling down.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)